Robert D. Putnam wants to have a debate without starting an argument. And he may succeed.

Robert D. Putnam wants to have a debate without starting an argument. And he may succeed.

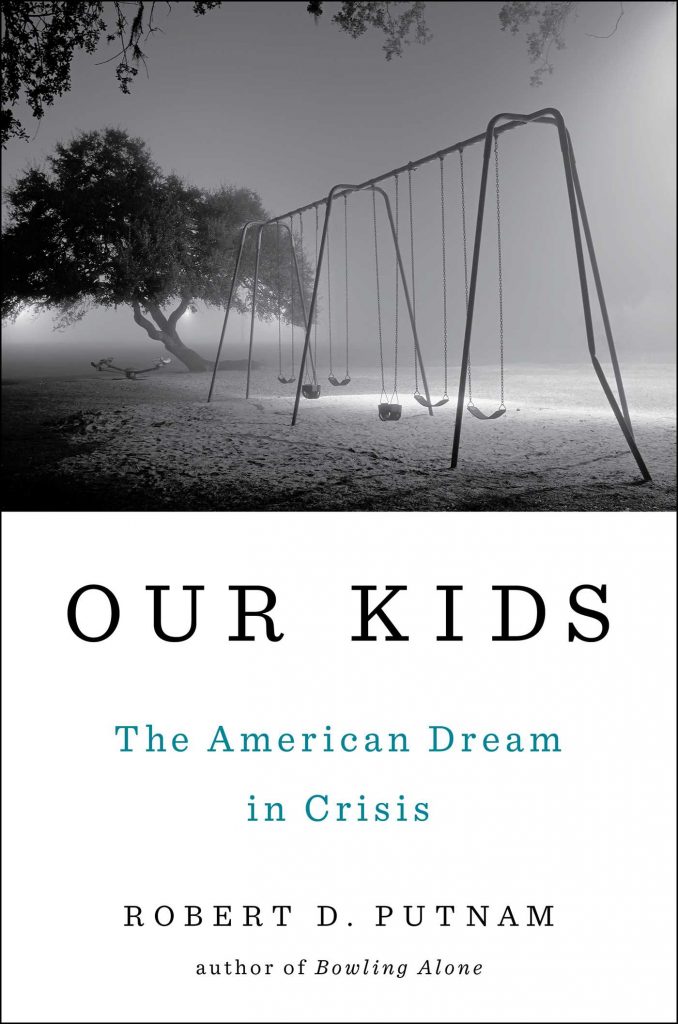

His new book Our Kids: The American Dream in Crisis succeeds in displaying the kind of canniness that makes the Harvard professor a favorite of both President Obama and Jeb Bush. To maintain the kind of equanimity that keeps your work at the heart of American political power, Putnam takes on the greatest and contentious economic challenge of our time — income inequality — using the widest and least controversial entry point imaginable.

We may dispute the motives of our fellow adults. “But to hold kids responsible for their parents’ failings,” Putnam writes, “violates most Americans’ moral sensibility.”

He further lowers the temperature of the debate by separating the issue into two: equality of income and wealth and equality of opportunity and social mobility. Given that conservatives generally believe that even mentioning the first set of issues verges on communism, Putnam largely focuses on the second set. And given that conservatives to varying degrees prefer to believe the greater crisis is making sure rich white kids can get into the college of their choice, Putnam wisely settles on the least contested concept — mobility, which is almost incontestably linked to the American Dream.

“About 95 percent of us endorse the principle that ‘everyone should have equal opportunity to get ahead,’ a broad consensus that has hardly wavered since opinion surveys began more than a half century ago,” he writes.

The most radical — and exceptional — achievement of the book is Putnam’s use of narratives to illuminate his research and generate empathy for working-class Americans.

He and his team begin with his classmates from 1950s Port Clinton, Ohio — “a passable embodiment of the American Dream, a place that offered decent opportunity for all the kids in town, whatever the background.” He then contrasts his experience to Port Clinton today, which suffers what he identifies as “a kind of incipient class apartheid,” that is truly one of the most tragic consequences of the end of segregation and the intentional hollowing of America’s middle class. Notice I use the word “intentional,” something Putnam never would. Instead he’s much more interested in forcing you experience the consequences of this hollowing.

In Bend, Oregon and Orange County, California and Atlanta, Georgia and Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, we meet two representative families — one that is hovering around the top 10 percent that has done fairly well over the past three decades and one from the lower 90 percent, where you are most likely to dip into Mitt Romney’s loathed 47 percent. Again and again, the families face crisis after crisis.

Again and again, the more well-to-do families thrive in their ability to navigate their context — which Putnam divides into families, parenting, schooling and community. All of the parents want the best for their kids and again and again the poorer families lack the resources and clear pathways to overcome their circumstances.

When one of the more affluent families faces the prospect of their child matriculating into one of the many struggling public schools in Southern California, they move closer to one of the many good public schools in Southern California. A divorced single mother in suburban Philadelphia faces a child with ADD and her job as a financial adviser gives her the ability to remodel her large home to give the child her own floor to study. Meanwhile, two twenty-something sisters live in their step grandfather’s house in Santa Ana, failed by their schools and only protected by the gang allegiances of parents they barely knew or know.

These stories are a true Rorschach test. The New York Times’ David Brooks read Our Kids and, while conceding that we need to change our policies, storms into a discussion into how we need to teach the better character so we can expect even greater heroism out of them, as The New Republic‘s Elizabeth Stoker Bruenig notes.

Why do we expect more heroism from the poor than we do from our society?

“Perhaps unexpectedly, this is a book without upper-class villains,” Putnam writes as he enters into a discussion about “What Is To Be Done?” After noting a recent study that notes that our current population of young people 16-24 who are neither in work or school will cost our society $4.75 trillion, his solutions are all rather small and palatable to many on the right, though left leaning.

All women are waiting longer to marry but poorer women are more likely to have kids earlier, to this Putnam suggests a variety of solutions including contraception, especially IUDs. Since this is a book without villains, he doesn’t note that access to such contraception has been expanded widely thanks to Obamacare, which Republicans are trying to repeal.

Putnam’s one piece of direct advice to readers moved by his stories, which almost all will be, is to make sure your school district’s sports teams are not pay-to-play, which — even if they offer waivers that shame kids — excludes poorer kids from extracurricular activities, which have astounding effects on producing better citizens.

It somewhat alarms me that one of his advisors called Putnam “Obama’s Piketty,” in reference to the French economist whose look at a century of tax data revealed alarming trends in inter-generational wealth accumulation. Whereas Piketty’s solutions may be too grand — a global wealth tax, anyone? — Putnam’s are too careful and judicious. He wants to give charter schools a chance without noting that many of these schools were built to undermine the community context poorer kids so desperately rely upon.

This is necessary to maintain a debate — which is just an argument without blame. And that isn’t possible when one side of the debate is proposing solutions that would make the problem worse.

But to get at the real reasons the lower 90 percent have been systematically drained of economic security and political power, you’ll have to read another book. I suggest Winner-Take-All Politics by Jacob S. Hacker and Paul Pierson.