This guest post comes from Sean McElwee — a research associate at Demos and an excellent follow on Twitter. Find out more about Sean, his work and what his research into voting uncovered about Michigan by checking out his first guest post for Eclectablog.

In my latest report, Why Voting Matters, I argue that nonvoters are more progressive than voters, and that higher voter turnout would dramatically change democracy. Though I’ve aimed to make the report relatively short and accessible (16 pages, and no academic language, I promise) I’ve laid out the core points below:

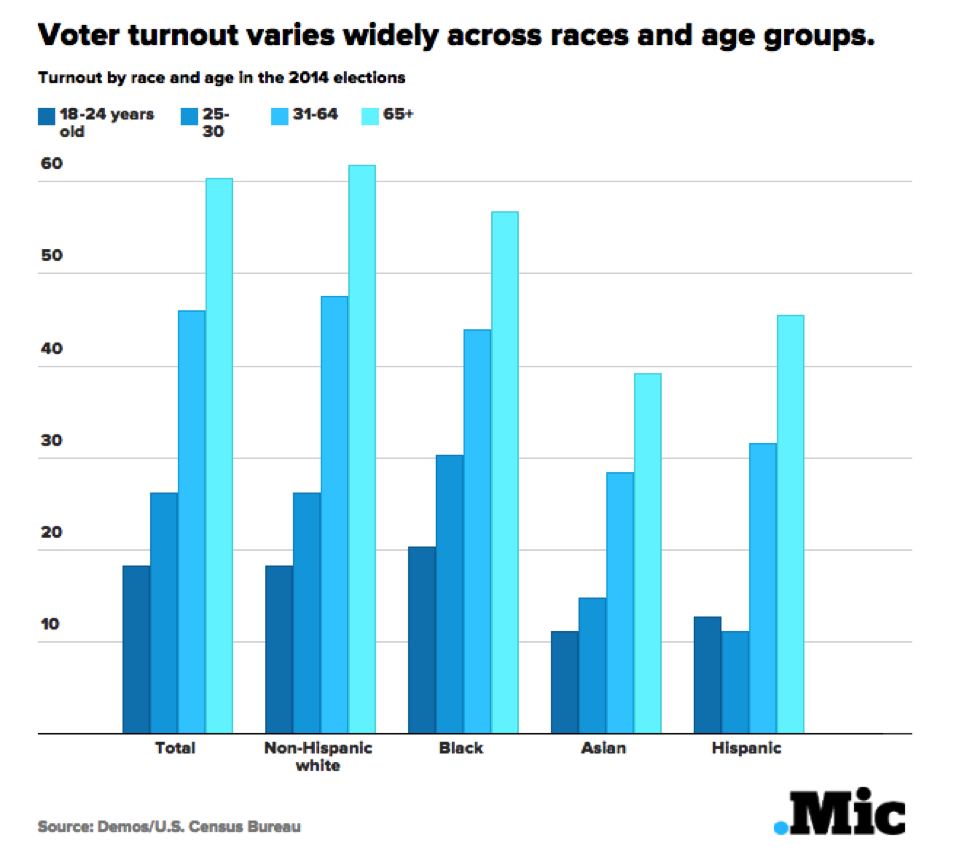

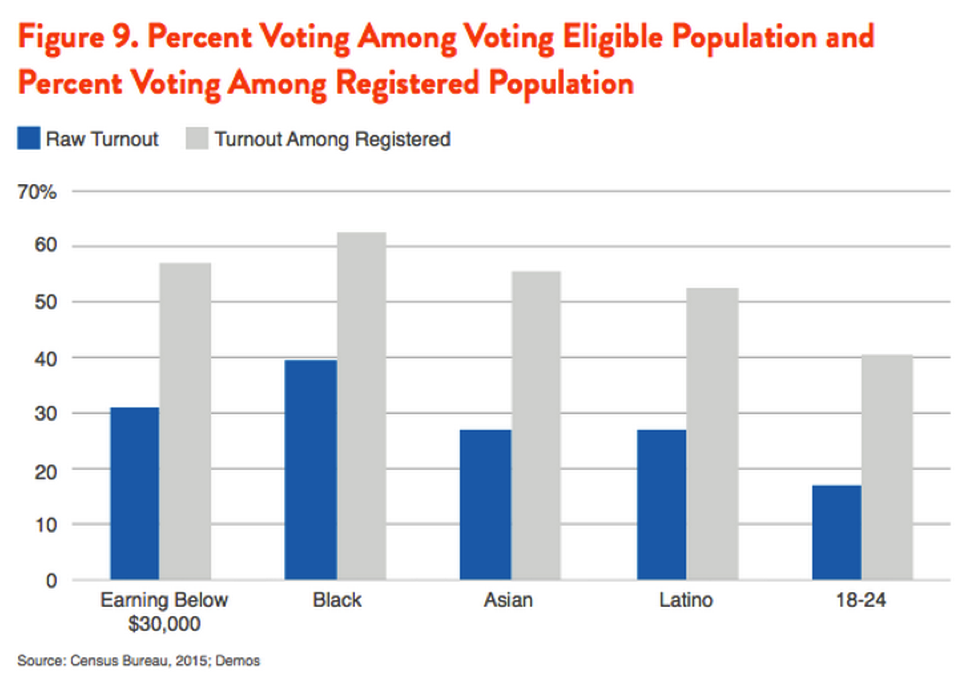

- Turnout Is Heavily Skewed By Race

In 2014, turnout among non-Hispanic whites was 46 percent, compared with 40 percent among Blacks, 27 percent among Asians and 27 percent among Latinos. Turnout is even lower among youth, Just 11% of Asian and 13% of Hispanic Americans between the ages of 18 and 24 voted in the 2014 midterm elections, meaning white Americans over the age of 65 were six times as likely to cast a ballot.

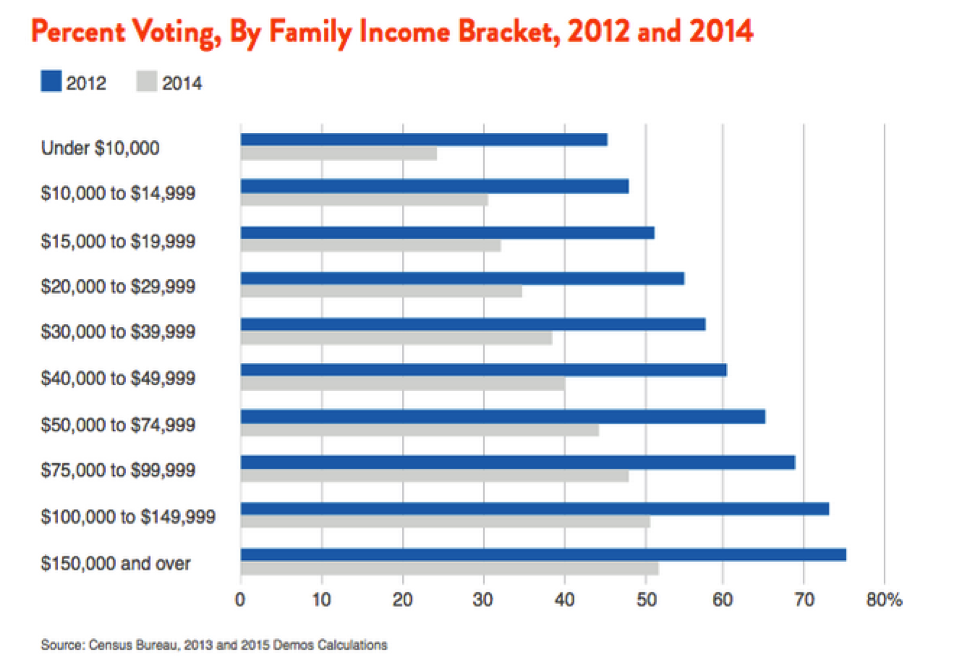

- Turnout Is Heavily Skewed By Income and Age

While 52 percent of those earning above $150,000 voted, only 1 in 4 of those earning less than $10,000 did. Class gaps are magnified by age gaps. Among 18-24 year olds earning less than $30,000 turnout was 17 percent in 2014, but among those earning more than $150,000 and older than 65, the turnout rate was nearly four times higher, at 65 percent.

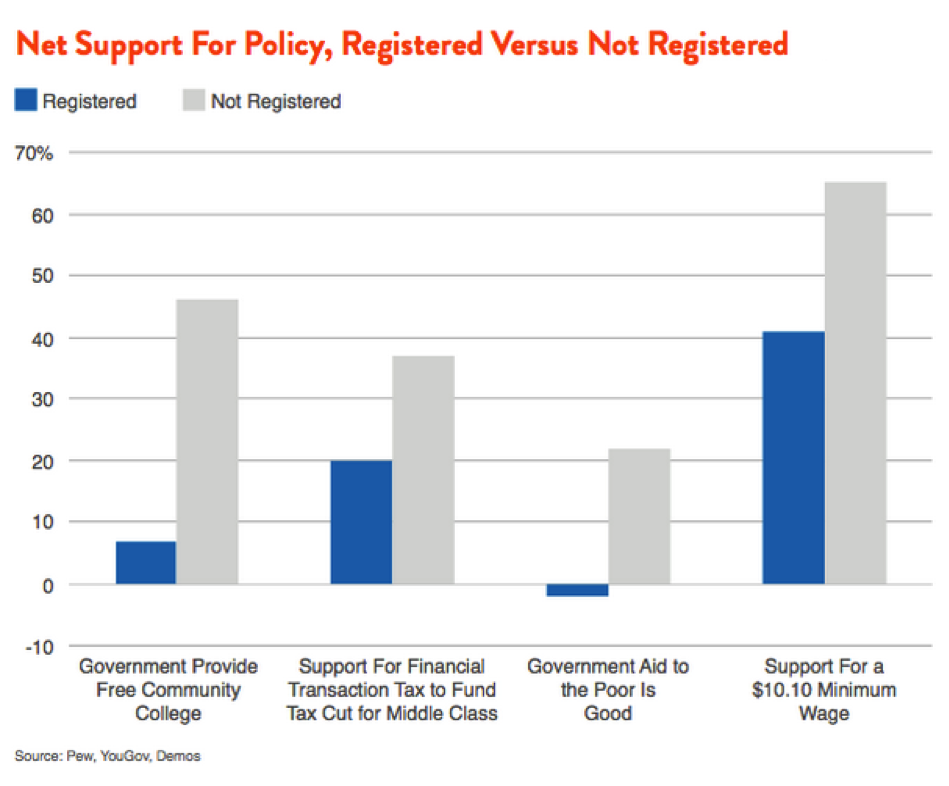

- The Registered Population Isn’t Representative of the Non-Registered Population

Using previously unanalyzed data from Pew and YouGov , I explored differences between registered and non-registered Americans. The results were incredibly strong: on all the issues I obtained data for, non-registered Americans, on net, were more progressive than registered Americans. This includes key questions, like debt-free higher education, a financial transaction tax and a higher minimum wage.

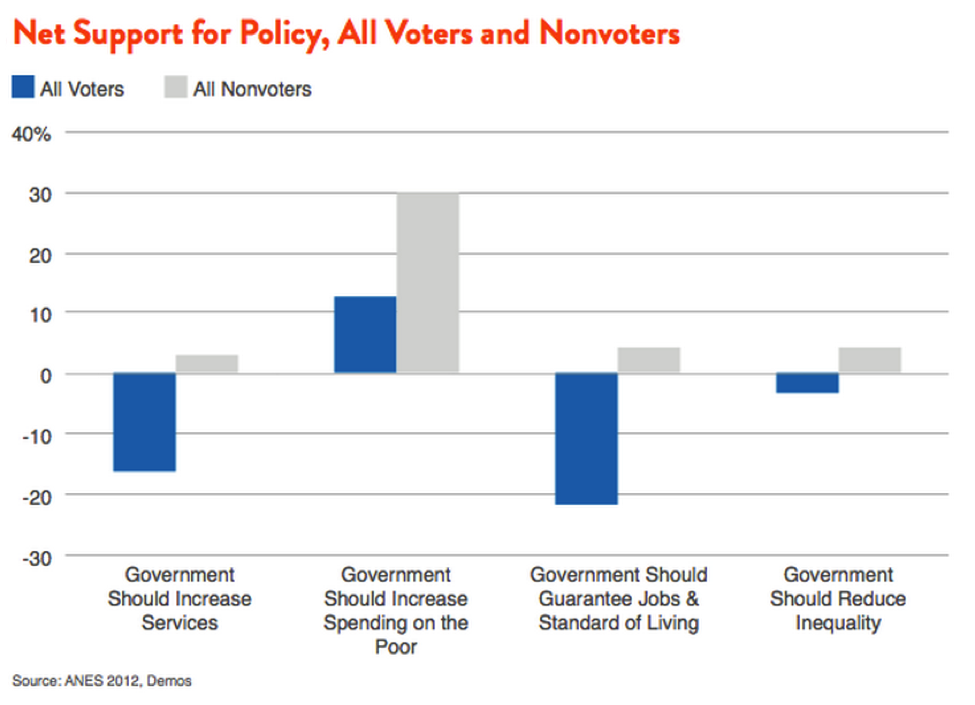

- The Voting Population Isn’t Representative of the Nonvoting Population

Using data from the highly respected American National Election Studies 2012 survey, I examined how nonvoters and voter compare on key issues related to the government’s role in the economy. I calculated “net support,” that is, I subtracted the percent of people who opposed the policy from the percent in support. As the chart below shows, these differences are strong, and on many issues, voters are opposed to a progressive policy, while nonvoters support it.

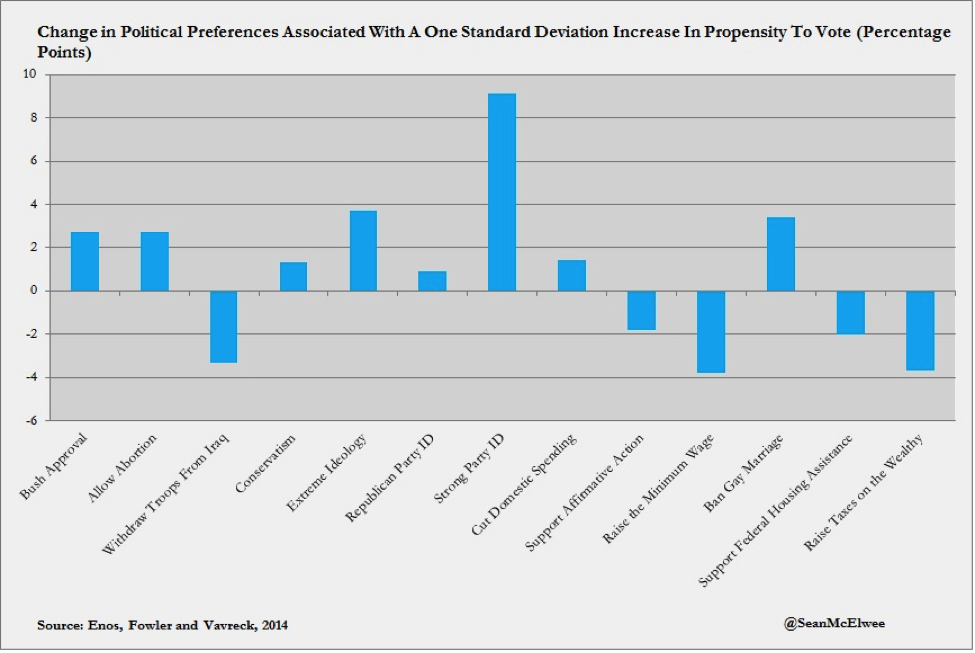

It’s not just the ANES data that show this result. As I discussed in Salon, a recent study by Ryan Enos, Anthony Fowler and Lynn Vavreck finds that a one standard deviation increase in the propensity to vote (15 percentage point increase in the chances of voting) is correlated with a $6,000 increase in family income, a 3 point increase in support for G.W. Bush, a 4 point decrease in support for a higher minimum wage, a 2 point decrease in support for affirmative action, a 2 point decrease in support for federal housing assistance. Their study relied on two different data sources: CCES (Cooperative Congressional Election Study) and CCAP (Cooperative Campaign Analysis Project). Three of the most trusted datasets in political science all showing the same result strongly suggests that these results are not spurious.

- Registration Barriers Are Key Impediments To Turnout

My report also examines what can be done to boost turnout. I argue that the most effective policies are those that will dramatically boost registration. There are numerous studies showing that registration reduces turnout, and that stricter registration practices exacerbate class bias and reduce the effectiveness of get-out-the-vote operations. As the chart below shows, turnout among groups that don’t vote frequently is much higher among those who are registered than those who are not. As I argue in the report, Same-Day Registration, robust enforcement of the National Voter Registration Act and implementing Automatic Voter Registration could all boost registration, and thereby turnout.

In the report, I dive further into the empirical studies about the impacts of turnout. I examine studies at the state level within the United States and international studies. I also examine the historical record: how women’s suffrage, the end of poll taxes and the Voting Rights Act affected policy. The findings are clear: more voter turnout leads to more progressive policies. Many people think that turnout will simply benefit Democrats, but I’ve argued frequently that the truth is more nuanced. In reality, higher turnout will force both parties to pay attention to the preferences of youth, people of color and low-income voters who they ignore in the status quo. The solution to concentrated wealth and power is more democracy.