“We had hundreds of people involved. There was a real community appetite for this process…they wanted their voice to be heard and they were prepared to come out and be a part of it.”

NOTE: Part 2 of this interview can be found HERE.

When Dayne Walling was elected to be the mayor of the struggling city of Flint in 2009, he knew very well what was in store for him. The city was bleeding population and its manufacturing core was gone, leaving an imploded city center with infrastructure to support without the revenues to do so. Still, Walling had a vision for reinventing the city and preparing it to adapt to change in the future.

Last month, Walling saw, perhaps, the most significant step forward for that vision when the Flint city council unanimously passed a new comprehensive master plan for the city. While many city and municipal master plans are passed every year, Flint has gone through a two-year process called “Imagine Flint” to arrive at this point. It was a process that was highlighted by effective and widespread community involvement. People representing every constituency in the city from residents to business owners and neighborhood activists to faith groups, the final plan is the result of a concerted effort to solicit community input at every step of the way.

Flint was under the control of an Emergency Financial Manager from 2002 to 2004. It’s now under emergency management once again and is in its second year under its fourth emergency manager. In some ways, the master plan process allowed Flint residents, who no longer enjoy locally elected government, to have a voice that is denied to them under emergency management. What’s also clear is that there is a dedicated, committed group of Flint residents that are determined that their city rise again and become a vibrant, livable, sustainable place to live.

I sat down for an interview with Mayor Walling this past weekend at his modest home in a tidy neighborhood near downtown Flint. We talked about the Imagine Flint initiative as well as his experience as a mayor living and attempting to work under emergency management. The interview is in two parts. Today, in Part 1, we discuss the Imagine Flint comprehensive plan in-depth and what it means for the future of Flint. Later this week in Part 2, we’ll talk about emergency management, where it fails, and ideas for a better plan forward for Michigan’s struggling urban centers.

Photos by Anne C. Savage, special to Eclectablog.

Tell me about Imagine Flint. It’s clearly been a really cool and involved process. How long have you been at it?

I came into office with a commitment to the community to put a long-term, comprehensive master plan in place for the city of Flint. It’s something the city hasn’t had since 1960. Through all of these turbulent times, the city of Flint has been flying blind when it comes to redeveloping for its future. Different individual plans, and there were a few coalitions that had plans, but there was nothing that had gone through the public process where the city of Flint adopted a comprehensive master plan. So, in the first budget that I proposed to city council back in the spring of 2010, I proposed that general fund dollars be made available to hire a chief planning officer, begin rebuilding the city planning department. When I came into office, there wasn’t a single urban planner on staff.

No kidding? When was this?

That was in the fall of 2009. Yeah, so the city’s planning department had been completely decimated. To the person. Most people, when I talk them, they still assume there must still be a planning department and there should be. But, no, there was not a single person with an urban planning degree when I got elected. And that is not acceptable. Not for a city that’s dependent on reinventing itself.

Unfortunately, that time, the city council did not agree. There was a debate about the general fund continuing to contribute to the sanitation fund, continue to offer a weekly garbage pick-up which I had discontinued for lack of funding. It wasn’t an easy decision to make but we were on an every-other-week rubbish collection cycle. City council, in their approval of our budget, and under our charter that’s where the authority lies to amend and approve the budget, we ended up not having the general fund resources to start the planning process.

Thankfully, about the same time, the federal Sustainable Communities initiative was getting going with the president’s leadership and there was an opportunity for us to apply for one of the Community Challenge grants. There were also regional grants for multiple county areas, but the Community Challenge grant was for either city comprehensive plans, or districts or neighborhood or corridor plans. So that’s what we applied for.

So they were actually incentivizing communities to do this sort of thing.

Yes. I think there were about 70 awards given in the first round and that was available when the president had a majority in the House and the Senate. The program hasn’t been re-funded beyond those first two years but we were able to get our Community Challenge grant award in place as part of the federal government’s sustainability, livability, inter-agency work. It came through the Department of Housing and Urban Development. It was about $1.5 million for three years and we pledged, based on our application and our coalitions, that we would come up with another $1.5 million locally. So, it’s an approximately $3 million, 3-year process.

The next largest funder is the Charles Stewart Mott Foundation. They have now invested over a half a million dollars in the process in grants to the city to use as match.

As part of the same strategic comprehensive planning process?

Right. One work plan.

So they were really encouraging and incentivizing cities and municipalities to do this sort of long-term planning. They saw this as something important for cities to do.

Yeah. I think the federal agencies saw two things. One is that there were a large number of federally-funded initiatives that didn’t have a required common framework to make sure that those investments were being done in ways that were aligned. There was also an intention of promoting a sustainability agenda, an equity agenda that federal agencies hadn’t previously been engaged with. So there was this livability collaborative and then there was the recognition that, for a city like Flint, we receive a lot of federal housing and urban development dollars, those need to be invested in a way that will add up long-term.

So, I made the announcement in 2011 that the city had received the grant. We didn’t have funds actually transferred until May of 2011, but we knew about the award a few months before that and I included that in my State of the City address. Then we started putting the pieces together and were able to start the grant in May or June.

One of the things that I’ll mention in terms of the three year timeline is that we committed in our work plan to do four phases of work: data and analysis on the front end, an extensive community engagement and visioning process, then the actual writing of the master plan, and the fourth phase was what we called an initial implementation. That’s a revision of the zoning code and the capital improvement plan.

Which is your next step, right?

Right. And those aren’t high profile activities in most communities but, if you want to have your plan really drive change, there has to be a way for people outside of city government to look in and see those rules and regulations and investments all being public investments and all being aligned. So, the lesson we learned from Youngstown, Ohio was, it’s wonderful to build community consensus and a plan, but if you don’t actually revise your zoning code and you don’t have a commitment from your department head and other elected leaders to make public investments in line with the plan, then the plan serves as a powerful vision but it doesn’t accomplish as much as it needs to.

Why do you bring up Youngstown?

That was one of the places that we looked closely at. They had done a high profile, successful planning process. A big component of that was recognizing that the city wasn’t going to double in population and become what it was 40 years ago. We had that same conversation here in Flint. Their situation was similar to ours but had hit about ten years earlier.

So, that’s the scope. We had to do the plan but we also had to be ready to go on the zoning revision.

At what point did the community involvement come in? In Phase Two, I’d imagine?

Phase Two, but really from the very beginning. We created a steering committee.

Another counter example is the process in Detroit where it was always a bit unclear whether it was being driven by Mayor Bing through Detroit Works or the foundations or the community partners. So, we decided to put everybody at the same table. We had a 21-member steering committee that included the co-chair and chair of the planning commission, two city council designees, and then a representative from each of the city’s nine wards. Plus business, faith, civic/community organizations and key partners like the land bank which owns a lot of property in the city.

That group got started right away in August of 2011. That’s when the community came together. I talk about this process because I’m someone who believes that processes and outcomes are linked. Often folks want to focus on processes or or they want to focus outcome. You’ll hear this when we talk about emergency management. My thinking about our public space is that it needs to be both oriented toward processes as well as outcome. We tried to design this planning initiative so that it was the right process but also got us the right outcomes. And that it was done in a timely manner.

So how long did the data collection phase last?

The data phase actually stretched longer than we thought it would in large part because of the uncertainty around the appointment of an Emergency Manager.

Ah, right. That happened soon after you got started, right?

Yeah. We were ready to make the transition after the initial planning work and hire the chief planning officer, bring on the consultant team in fall of 2011 but we had the review process started in August of 2011. Then there was not only my reelection but also the announcement of the Emergency Manager.

That’s right. You got elected and then basically lost your job a week later!

That’s right. Treasurer Dillon called me at 3:30 on election day to say that they were appointing an Emergency Manager for Flint. So that bumped us forward. The chief planning officer ended up starting in March of 2012.

Was this process you were going through something you could use to argue against an Emergency Manager? It seems like this would have been evidence that you were working to turn things around.

There really wasn’t much debate about the appointment of an Emergency Manager. I certainly couldn’t argue that the city wasn’t having a financial issue. That was why I had run against the previous guy and that was before the recession hit. So the deficits were unwieldy. I always saw it more as a prerogative of the governor and this Republican legislature; that, if this was their solution then, frankly, there really wasn’t much anyone could do about it. And I think the courts, with all the court cases that have been filed, that’s basically proven to be true. There may be an exception here or there but, generally, cities are creatures of the state.

They’re chartered by the state.

Right. However, the other side of that coin is that the state should be responsible and play a nurturing role. Right now we have folks that want to have it both ways.

Talk a little bit about the data collection phase and how you moved into public input.

With the steering committee in place to guide the process, our partner organizations like the Mass Transportation Authority, Flint community schools, the land bank, the city of the Flint, we all started creating what was called an “Existing Conditions Report”. That was more than 100 pages that had all the key data on everything from public safety to infrastructure. In the document you can see it, there are eight technical chapters that go with the plan. So, we were collecting data and working in every one of those areas.

The real task of the steering committee was around community engagement. From the beginning that group was talking about what we needed to do to engage the community in a serious way. In December/January of 2012/13 we did a round of initial community input sessions where folks were asked about their top five priorities, what if you had to pick just one, that sort of exercise.

How big of a response did you get from that? I was on a planning commission in Meridian Township and it was often hard to get people to show up to those sorts of things.

Oh, no! Not us! We had hundreds of people involved. There was a real community appetite for this process. Hundreds of people showed up at these initial sessions. And then, in order to coalesce all of that diverse feedback from multiple meetings, we decided to have one large community summit. We contracted, through our consultant team Houseal Levigne, with America Speaks. America Speaks is a national civic engagement company that did work Washington, D.C. when I worked for Mayor Tony Williams, did work after Katrina in New Orleans, and after the 911 World Trade Center attack in New York City. They worked with us on a one-day summit that would, in a very public fashion, put 500 people in the same room and have them talking together at small tables. They were also doing keypad polling on specific questions so you could see in the room what’s happening and who agrees with what. We called it our Community Vision and Goals Summit.

That was march of 2013. There’s a picture of it on our website of the huge crowd we had. This was a Saturday in March and more than 500 people came out.

I saw that picture. I was really impressed.

They got there at 8, 9 o’clock and stayed until 2, 3 o’clock and it was in the midst of the city being under an emergency manager. It was a really powerful testament to how people were feeling.

That had to have been helpful. I mean, maybe in some ways, that was the only voice that people had into their government with the Emergency Manager there.

I think you’re on to something.

It’s an interesting side effect that Emergency Managers created — I mean it’s hard to get people to get involved — but it created a situation where people wanted to flex their democratic muscles a little bit.

There’s a core group in every community that naturally wants to be involved shaping their future and, when one path is taken away, there’s energy available to go in a different direction. But, I have to say, too, that this public discussion about the master plan had been out there for a long time. I suspect there would have been a very large turnout and engagement regardless, really. But, because it happened while there was an Emergency Manager, it really showed that the people wanted this. They wanted a plan, they wanted their voice to be heard, and they were prepared to come out and be a part of it.

That was what established our guiding principles around sustainability and equity, diversifying the economy, quality of life, investing in youth, having an accountable civic structure, and adapting to change. So, out of all of the different discussions that took place, there were six guiding principles that were distilled from the discussion. Everything in the plan has to relate back to those guiding principles and you see, in every chapter, the objectives are coded by which guiding principles they speak to.

The community established the framework. They didn’t go to some secret committee to decide what to write. Whatever we walked out of there with that day was what we were going to work with.

How democratic!

It was highly democratic!

When did you start writing the plan?

Coming out of the community summit, our consultants and our planning staff started working with our advisory groups which had been in place a few months prior doing exploratory work around the existing conditions. Each of the six advisory groups, plus there was a seventh through a federal NEA grant around arts and culture, they all started looking at the guiding principles and then figuring out what the goals and objectives should be in their respective areas: housing, neighborhoods, transportation, and infrastructure.

We had over 150 people participate in the advisory groups. These were everything from a neighborhood activist to a university expert that’s here in the Flint area.

What about the development community? Builders, developers, folks like that? One of the tensions that we had when I was on the planning commission was that the developers had a significant presence in terms of the plans we were looking at. They tended to drown out some of the people that were in the local communities at times.

The developers, both economic and community developers, were at the table. I think they were respectful of the process and participated in a constructive way. There has been some tension between a couple of projects that were already underway and different people’s perceptions of how well-aligned those projects are with the master plan. But, we said from the beginning that we’re not putting this city’s life on hold for three years while we write this plan. We’re going to have to make decisions as we go and just do the best we can. I guess we’ll know that this plan has been successful if we get to the point where we’re arguing with developers at some point in the future!

So, what’s next? What are your next steps? You’ve got some rezoning to do, I know…

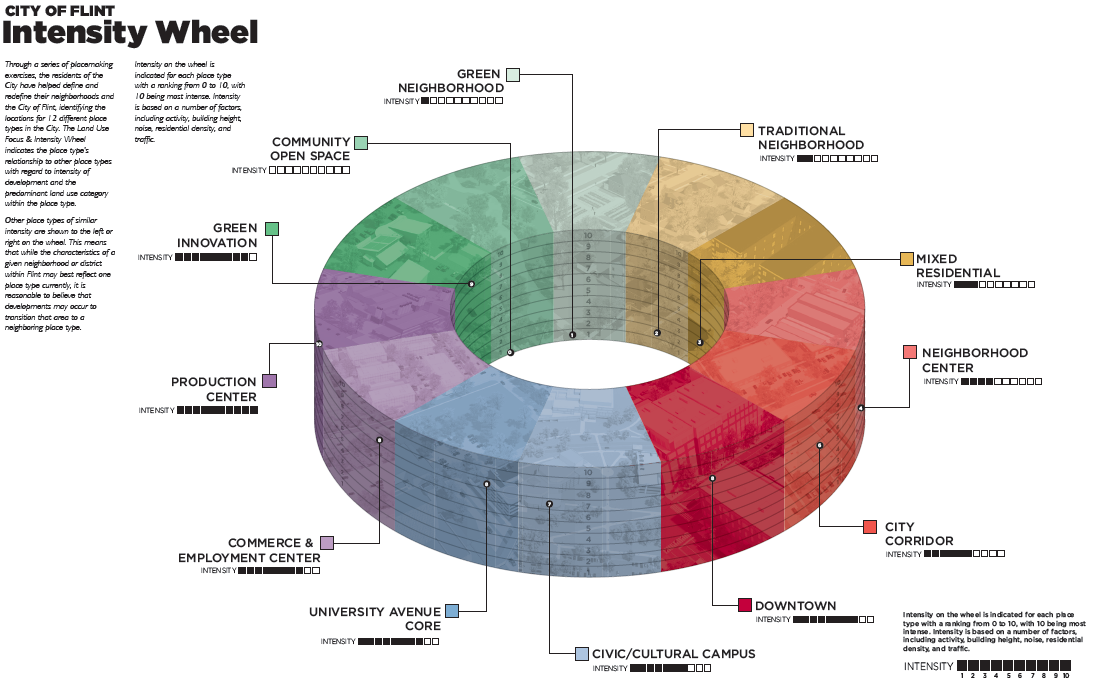

Yes, one of the core innovations in the plan is idea of building communities through place making. That’s a methodology that’s being promoted often in relationship to “downtown” or smaller, mixed use areas. We created 12 place types that are all represented in our land use map. Now, through the zoning code, the details of those places have to be worked out.

This sounds a lot like the “Economics of Place” ideas that Dan Gilmartin writes about.

We looked very closely at that. But, we’re also trying to apply it to traditional commerce and industrial areas as well as to lower density, green neighborhood areas. So, the idea, really, is that place is a combination of people and policies and infrastructure and programs. You want all of that to work together in a way that will provide for a high quality of life whatever your physical environment is — more dense, more urban, more rural, more suburban. That’s what we’ve got to do now: go in and completely rewrite our zoning. Of course, existing uses will continue to be allowed and we’re going to be pretty flexible on that in areas where we’re proposing a very different use than the current one. There have been a few neighborhoods that have been coded as green innovation which we see as an economic use, not as a residential use. So, that’s going to take time. There is no relocation in this plan and there is no cutting off of city services. We didn’t hear that from the community and it didn’t come from the advisory groups so that’s not part of this. But there are some very radical land use changes that are in the plan that we have to manage over the next five to ten years.

I’ve seen some comments about whether there is going to be enough money to implement this. What are the types of things that would require funding and financing and where is that money coming from?

Well, the first thing the plan will do is let us coordinate and align existing resources. For all the talk about the city being broke, we make $200 million in expenditures on an annual basis so there’s a tremendous opportunity for those existing dollars to have a greater impact as long as they’re targeted and aligned and we have a program that we follow over the next few years.

Every chapter has a implementation matrix that has short, medium, and long term notations as well as one to four dollar signs, kind of like a restaurant guide. So, the idea is that, in the next five years, if we focus on things that are short term with one or two dollar signs, we should be able to get that done with existing resources from ourselves and our partners including the foundations that already make tremendous investments in this community.

Then, as we work on the revision of the plan, because now we’re going to do this right under Michigan law and revise it every five years, we can reset that implementation matrix and look at things that are a little farther down the road. So, I actually think it’s a misconception that funding for individual projects is Flint’s challenge.

I’m glad to hear you say that because that was the sense that I got from some of the comments in the media, that, “It’s great plan but they’ll never be able to afford that.” I didn’t understand why this would take so much money. The individual projects, yeah, you’ll have to go out and find that funding. But, in terms of the creation of the comprehensive plan and the rezoning, those aren’t things that take a lot of money to do. It’s a process that you’re going through anyway.

The second level is that I think the existence of the plan will allow other entities that may not be maximizing their investments now to increase those because now they can see which intersections, which corridors, which areas are primed for new development. For example, an agricultural community can look at the map and see where we want to grow large scale urban agriculture over time and they can invest in those places so that we don’t have a conflict three years down the road when something becomes successful but it’s now going to be taken over by the company next door.

Those are the two things that I see. There’s no doubt that we’ll be looking for money for individual projects. And there’s also this fundamental financial system that’s broken in municipal governments in Michigan. But, that’s not about funding for the master plan. That’s about a stable source of revenue for governments to work. We still do need to solve that problem. But we’ve got resources for some projects and now we’ve got a blueprint for others to look at and invest in.

It strikes me that this would increase your chances of being able to secure that kind of funding for projects because now you can point to this and say, “Look, this isn’t just throwing money at a problem. This is directing very targeted money at a specific part of a solution that we’ve come up with as a community.” It should enhance your opportunities to get those kind of grants, I would think.

Right. Exactly.

It seems like the response has been pretty favorable in the media. What’s your sense from the community itself?

I think the citizens all let our a sigh of relief and a round of applause when they saw a unanimous vote from the planning commission and the city council!

How many people were there when that vote went down?

We had over 100 people at the city council meeting. The week before at the public hearing for the planning commission, ten days before, we had over 200 people there. There was a quite a lot made of “this is your last chance before the planning commission votes to adopt” so that was almost a full house in city council chambers. Then the commission met a few days later with a smaller crowd, probably 40 or 50 people, when it was adopted. Then we were back up to about 100 for the historic vote from city council. There’s always some surprise up at city council and this time it was a good surprise with a unanimous vote.

So, that tells you something. When you think about the diversity of the city with respect to race and class and age; for that city council leadership and planning commission to all look at it and say, “this is the vision we want for the future” is pretty incredible.

Does this plan take into account the drop population that Flint has had? In 2000 it was 125,000 and now it’s just a bit over 100,000. This plan accounts for that?

We peaked in 1970 with about 200,000 and we’ve dropped from there to just over 100,000 in 2010.

And then over the next two years you lost 2,000 more. How does your plan take that trend into consideration?

The density guideline that’s in the plan shows our green place types will be much less dense than when they were built or when they were at their maximum capacity 40 years ago. But, we do also work to create these more dense, walkable mixed use environments that should draw some folks into the city, give our seniors some different options than what they have right now, and keep people in the city who are already here in a healthy living environment.

We will continue to lose some population over the next few years. But, with the right state and national economy, we could stabilize and even begin to grow slowly. The density guidelines for the place types can accommodate a population anywhere between about 80,000 and 120,000 with this plan. You could have a little more density or a little less density and still have essentially the same overall quality of life.

That’s how we tried to look at it, through that principle of how you adapt to change. This city has gone from being a trading post to a lumber village to a carriage town to this automotive powerhouse and that’s all been in 150 years. We’re going through another transformation now and we want to recognize that in the long term plan, that there will continue to be change but to have the flexibility to adapt to it.

In the plan, there’s a wheel that shows how the different place types relate to each other so that a future planning commission can dial up or dial down the density and still maintain the integrity of the plan.

You can learn more about the Imagine Flint project by visiting their website HERE. There you will find overviews as well as a comprehensive collection of planning documents that comprise the master plan in full.