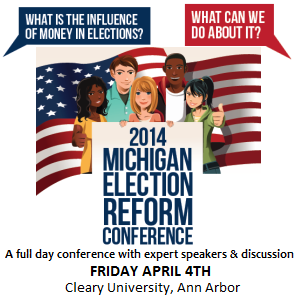

A week from today on Friday, April 4th, 2014 the Ann Arbor-based group Reclaim Our American Democracy (ROAD) is holding their 2014 Michigan Election Reform Conference at Cleary University in Ann Arbor. You can have a look at the brochure for this important event HERE (pdf). Registration is only $25, $10 for students and you may purchase a boxed lunch for $10 (deadline is Monday for ordering the lunch.) You may also register at the event for an additional $5. Click HERE to register.

A week from today on Friday, April 4th, 2014 the Ann Arbor-based group Reclaim Our American Democracy (ROAD) is holding their 2014 Michigan Election Reform Conference at Cleary University in Ann Arbor. You can have a look at the brochure for this important event HERE (pdf). Registration is only $25, $10 for students and you may purchase a boxed lunch for $10 (deadline is Monday for ordering the lunch.) You may also register at the event for an additional $5. Click HERE to register.

The conference features an all-star cast of participants:

- KEYNOTE SPEAKER: Josh Silver – Director of Represent.Us

- Ian Vandewalker – Counsel for the Democracy Program at the Brennan Center for Justice at the NYU Law School

- Jocelyn Benson – Interim Dean of Wayne State Law School

- Rich Robinson – Executive Director of the Michigan Campaign Finance Network

- Jim Townsend – State Representative, MI-26 (Madison Heights/Royal Oak)

- Jeff Irwin – State Representative, MI-53 (Ann Arbor)

Yesterday I spoke with Josh Silver from Represent.Us about his organization and about his keynote speech. I first met Josh when he and his team came to Michigan to drop fake money onto State Representatives on the House floor last fall. At the time, Silver had this to say:

Woefully inadequate or nonexistent campaign finance, lobbying, and financial disclosure laws make legalized bribery the law of the land in Michigan. The state is among the most politically corrupt in the nation, and legislators should be ashamed. Instead, state lawmakers continue to block the most basic, common sense anti-corruption reforms that are strongly supported by conservative, liberal, and independent voters across the state. Money talks in Michigan, so we decided to speak to House members in the only language they seem to understand.

Here is video that I shot of the event:

Next week, Josh Silver will be back in Michigan to talk about strategies for defeating the corruption of our elections and government by money. Here is our interview:

Thanks for taking some time to talk to me today, Josh. First, can you give us an overview of Represent.Us, what the group does, that type of thing?

Sure. Represent.Us is a new campaign — it’s a little over a year old — that is focused on winning a national political strategy to address the undue influence of money in U.S. politics. We’re doing that by building a campaign around a set of new strategic assumptions about what needs to happen in order to actually win. There a six assumptions:

Sure. Represent.Us is a new campaign — it’s a little over a year old — that is focused on winning a national political strategy to address the undue influence of money in U.S. politics. We’re doing that by building a campaign around a set of new strategic assumptions about what needs to happen in order to actually win. There a six assumptions:

- That politicians are not going to fix the money in politics problem unless we force them to.

- That forcing them to is going to require a big grassroots political movement.

- That movement must be comprised of grassroots progressives and conservatives because both strongly favor reform in this sector. There’s a ton of cross-ideological support and, frankly, progressives, who have largely been leading the charge on money in politics reform for decades, well, there just aren’t enough progressives to win. They need the conservatives.

- This is not going to won just through a single, incremental approach like just a public funding bill or just a transparency bill.

- The movement must be reframed around corruption, not around democracy, money in politics, or campaign reform.

- We have to start by passing state and local anti-corruption laws around the country, much like the marriage equality and marijuana reform issues. Neither of them stood any chance in Washington so they took the fight to the states.

That’s interesting. You mentioned not using “democracy” or “money in politics” as the focal point. That sort of separates you from groups like Move to Amend or Common Cause. Would you agree with that?

I think most of the groups are shifting. I think you’re seeing groups like Common Cause and Public Citizen and others talk about corruption more. But, then again, different groups have different demographics, right? For example, Common Cause does great work in the space that they’re in and uses the message that works for them.

We just conducted a poll in Montana with 500 people statewide and we asked voters, “Is important to you to address the influence of [fill in the blank] in elections?” When we replaced the word “money’ with the word “corruption” we saw a 30 percent jump with conservative voters. That’s huge.

You can’t ignore that.

Yeah, you ignore that at your peril.

How much success are you having reaching out to people who call themselves conservatives?

We’re having really good success. We did a survey of our Facebook following and over half of them are self-identified conservatives. In the Montana poll, the pollster — he’s actually a progressive pollster, Paul Harstad out of Colorado — he said in 32 years he’s never seen as strong of support for a ballot initiative as he did in ours.

The other part of what we do that’s different is that we concluded that the majority of efforts to address money in politics across the country historically that have approached this legislatively — as opposed to the constitutional amendment folks — the legislative approach has been mostly around public funding of elections. There are two problems with that. Number one, public funding in and of itself is not particularly popular. And, number two, I believe, speaking for my organization and myself, that public funding alone, without ethics and lobbying reforms and transparency reforms does not actually have the desired outcome that many campaign finance reformers desire. I say that as a veteran. I was the campaign manager for the 1998 public funding ballot initiative in Arizona that won.

What we find is that, if you take these other provisions around ethics and lobbying and transparency and you combine them with public funding, you then enjoy the enormous popularity — 83, 85% popularity — of the ethics and lobbying and transparency provisions that kind of create a bubble of support that you can fit the public funding into. It’s a really effective political strategy.

It seems like a lot of the really wealthy candidates or the ones that are supported by wealthy donors just sort of bypass the whole “public funding” thing and fund their campaigns themselves. We’re seeing that here in Michigan.

Yeah, that’s right. But the laws we’re creating in the Anti-Corruption Act, for example, say things like politicians can’t take money from the interests they regulate or that extend the revolving door between public service and lobbying and they redefine lobbying. These things, in many cases, limit how much lobbyists can give to politicians. In the aggregate, these things have a really positive effect on policymaking, even in the day of the SuperPACs.

How do the SuperPACs fit into this in terms of what your goals are?

There are two things we’re trying to do. One is an easier lift than the other. The easier lift, the more doable lift is to strongly redefine the definition of what it means to “coordinate” between the SuperPACs and the candidate campaigns. Because, as you know, today it’s a joke, right? You have the Supreme Court saying, “Yeah, the SuperPACs are okay because they are independent of the campaigns.” But, on the other hand, literally every day in the press you will regularly see “Mitt Romney’s PAC” or “the PAC supporting Barack Obama” or the governor or whatever. It’s overt.

So, tightening those up is one. The other is, if you’ve been a staffer on a campaign or you are a family member of the candidate or your firm has worked for the candidate, there are rules. If you worked for the candidate then you cannot go to work for any SuperPAC that spends money in support of that candidate. If you’re a family member, you can’t go work for the SuperPAC. If you’re a high-power political consultant or a firm that has a big contract with the SuperPAC, for example, then you can’t go and suddenly start working for the candidate, as well.

These are really commonsense things that don’t exist today.

So you’re focusing on that kind of reform at the local level?

Yes. What we do is to take the nine or so provisions that you can read about at AntiCorruptionAct.org and, whichever of those provisions in the federal act that are applicable and appropriate for a state, we then modify our proposal to create a statewide law. We include whatever makes sense. And, likewise, we’re also doing that for municipalities.

So that’s the next step for us. The first year was building public support and now we’re getting ready to start moving forward.

The other thing that I would mention is that none of this, whether it’s our proposal or any of the others, none of them have any chance of passing federally any time soon, as you know. So, what we’re all about now is building a big, loud anti-corruption movement that can float all boats including those who are advocating constitutional amendments or comprehensive legislation or what have you.

Let’s talk a little bit about the conference next week that you’re participating in. How did you hook up the Reclaim Our American Democracy folks?

Well, as you know, we were coming to your state to do a money drop because Michigan has the dubious honor of being one of the top five ranked “most corrupt state political systems”. So we targeted it for a money drop which we did by dropping fake money on top of the heads of the Michigan state legislators. In doing that, we reached out to local activists and came across [ROAD Chair] Stu Dowty and a few other folks. They were really helpful with the money drop, we got to know each other, and I think they really liked the idea of using the upcoming conference in Ann Arbor to talk about some fresh stuff, some new ideas that are happening. I think we represent sort of a different way of thinking when it comes to how to win on this issue.

Well, as you know, we were coming to your state to do a money drop because Michigan has the dubious honor of being one of the top five ranked “most corrupt state political systems”. So we targeted it for a money drop which we did by dropping fake money on top of the heads of the Michigan state legislators. In doing that, we reached out to local activists and came across [ROAD Chair] Stu Dowty and a few other folks. They were really helpful with the money drop, we got to know each other, and I think they really liked the idea of using the upcoming conference in Ann Arbor to talk about some fresh stuff, some new ideas that are happening. I think we represent sort of a different way of thinking when it comes to how to win on this issue.

I would agree with that. You did those money drops in other places, as well, right?

Yeah we did one in New York and another in Springfield, Illinois, for example.

How effective was that for getting attention for the cause?

Good for getting local attention. We had hoped that by the third or the fourth we’d start to get national attention but that didn’t happen.

Do you struggle with that in terms of getting media coverage for this issue?

Absolutely. Big time. The problem is that political reporters are sort of inured to it. Daily corrupt quid pro quo politics have literally become the norm and they are largely legal. The system today is legalized corruption. Because it’s legal, it’s not a story, so to speak. It’s like, “Hey, that happens every day. Where’s the news here?”

This is a problem from a journalistic point of view. It’s one of the classic challenges for a journalism field that is starving for coverage because so many journalists have been laid off. It’s a field that’s both cynical and terrified of being branded “the liberal media”. In this question of what constitutes a story and what doesn’t, it’s really a travesty when you have to see the FBI arresting the mayor of Charlotte, North Carolina or a state senator who is running for Secretary of State in California, two things that have happened in the past 48 hours. These gross illegal activities are the only things that get anyone’s attention.

No kidding. It’s actually opened up a niche for citizen journalists to step in fulfill that role although they don’t have nearly the voice of a local newspaper or a statewide newspaper does.

Talk about your segment at the conference next week. It’s titled “Political Power and Common Ground: Forging a Path to Victory”. What are you going to be covering there?

I’m going to be talking about the need to build a national anti-corruption movement. One of my big messages to a group like this where the people are going to be fighting with all sorts of approaches from constitutional amendments to narrow, tailored legislation to ethics reform, or what have you, is that those differences in policy objectives don’t matter in the short term. What I’m going to challenge people to do is to become part of a national anti-corruption movement because it will advance their policy objectives, no matter what they are. We don’t need to squabble over whether an amendment is smarter than legislation or if comprehensive legislation is better than incremental. Those things don’t matter because we don’t have any power. Until we get power, we’re not going to win anything. And, in order to build power, we need to build this anti-corruption movement.

It’s going to be sort of a call for people to join ranks and do that together for, really, the first time in our country but following in the footsteps of the suffragettes and the civil rights movement and the environmental movement of the late 1960s and early 1970s and, more recently, the marriage equality movement. We need to look to these experiences as a model.

Do you think you’ll get a welcome from the other major national groups in terms of that sort of approach?

I do, but, of course the politics are always a bit tricky. I mean, we’re the new guys and there is competition for philanthropic funding. Our arrival might imply to some people that what’s being done now is not sufficient. But I believe that we do need new strategies and do think that, over time, you’ll see some of the other major national groups increasingly adopting our position because it really makes sense.

It sounds like you’ve got the data to back it up and that’s important.

Yeah, for sure.