The Republican Party’s first convention took place “under the oaks” in Jackson, Michigan on July 6th, 1854.

A crowd of three thousand felt-hatted Free Soilers, top-hatted ex-Whigs and hatless abolitionists* gathered in the summer’s wet heat for a day to organize in protest of the Kansas-Nebraska Act, which had shattered the fantasy that America could survive a half-slave and half-free.

Only two years later, the party nominated its first presidential candidate. In 1860, Republican Abraham Lincoln became the first president elected to oppose the expansion of slavery. On the December 6, 1865, the thirteenth amendment abolished slavery.

As far as American creation myths go, it’s hard to top that. You’d probably have to be bitten by a radioactive bald eagle to have a chance.

Since I discovered that the party I love to hate was born in my adopted state, I’ve spent a lot of time (too much time as you’ll be able to tell from the length of this post that’s too long to ever be read on the internet) looking into why it happened here, after the party’s first unofficial gathering in Wisconsin the year before.

What I’ve discovered gave me renewed faith in our always-stilted political system and reminded me how a true grassroots movement bent on righting an injustice can transform this nation, even at the bleakest points in our history.

While prim Puritans and quirky Quakers of the northeast had despised slavery since long before the nation’s founding, it’s no coincidence that the birth of the GOP along with many of its first victories occurred in the state preferred by four out the five Great Lakes. The Underground Railroad carried thousands of escaped slaves through Detroit to Canada. The Signal of Liberty, a pioneering abolitionist newspaper, was published out of a safe house in Ann Arbor. Pennsylvania Quakers migrated to Cass County in southwest Michigan, creating a haven for blacks who had escaped or been freed from bondage.

But the episode that made Michigan the lightning rod of the anti-slavery movement has been mostly forgotten by history—probably because Brad Pitt hasn’t made a movie about it yet. This clash pit citizens whose jobs and worldview depended on slavery against those whose morality would no longer abide it. It’s a story everyone should know, and it all began with what some call the first shot of the Civil War.

But this “shot heard round the world” was fired by a free man who would not be bound in chains again.

–§–

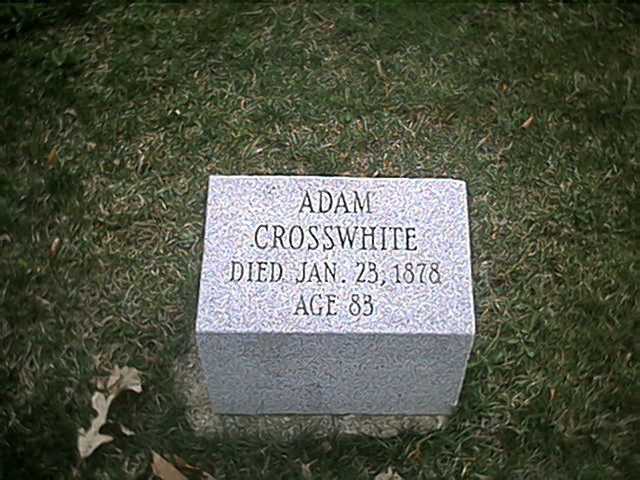

Like many of those born into slavery in America’s south at the beginning of the nineteenth century, Adam Crosswhite’s first master was his father**.

At only a few months old, the boy was taken from his slave mother and given to his father’s free white daughter to act as her servant. A few years later, he was purchased by a local trader then sold again and again. In 1819, Francis Giltner of Carroll County, Kentucky bought the now-twenty-year old man for $200, which in today’s money would still be a trifling amount to pay for a human being’s life.

On the Giltners’ 80-acre farm, Adam started a family with Sarah, a fellow slave. His master rewarded his decades of loyalty by making him an overseer.

In August of 1843, Adam learned that John, the oldest of his three children, was to be separated from the family and sold. The sale of one’s children was just another abomination slaves were forced to accept without protest. But for Adam, the notion was intolerable. As the plantation slept, the family fled. They crossed the Ohio River on a skiff and followed to the North Star to Madison, Indiana, a hub of the Underground Railroad’s “Quaker Line.”

When the Glitners discovered slaves were missing, Francis’ son David and Francis Troutman, a grandson of the man who sold Adam to the family, formed a posse. Under authority of the Fugitive Slave Law of 1793—which protected masters’ rights to their slaves anywhere in the United States—the men and their bloodhounds tracked the Crosswhites for hundreds of miles north. Giltner and Troutman caught up with the fugitives and their twenty armed escorts in Newport, Indiana.

Outnumbered, the Kentuckians could only watch as Railroad’s conductors sped the family away.

The Crosswhites remained in hiding until the posse gave up and headed home.

Free again, Adam, Sarah, John, Benjamin and Frances were sent through Illinois then on to Marshall, Michigan, where they waited for their passage to Canada.

A few dozen ex-slaves had settled just outside the little town, creating a tight-knit but welcoming community. There the Crosswhites enjoyed ordinariness of freedom for the first time in their lives. Adam and Sarah decided to stay.

Within weeks, they took a mortgage for a house on East Mansion Street. Adam worked as a carpenter and a mail carrier as the children attended the village school, already racially integrated more than a century before Brown v. Board of Education.

Images of northerners flouting the law, depriving law-abiding citizens of their constitutionally protected human chattel, obsessed Francis Troutman. He became a lawyer and in his spare time, he collected reports of escaped slaves living free lives under tacit protection of the local northern governments. In November of 1847, he presented his findings to Francis Giltner and other aggrieved planters. They agreed to fund the lawyer’s mission to act as a LoJack for their missing slaves.

The stranger—let’s imagine him wearing an awful fake horseshoe moustache—told the proprietor of Marshall’s local inn that he was considering relocating to their community and would be exploring the area for a few days. The innkeeper introduced him around. Troutman quickly befriended a sheriff, Harvey Dixon, who introduced the stranger to several residents of the town’s black community. One of Adam’s neighbors unwittingly revealed the Crosswhites tale of escape along with their whereabouts.

He concluded his investigation by paying Dixon five dollars to pose as a census enumerator. John Crosswhite answered the door and offered the family’s names to the official.

The next day, Troutman, thrilled to have a second chance to hunt the Giltners’ “property,” returned to Kentucky with his evidence.

Before long, the residents of Marshall began to make sense of a lone southerner’s sudden interest in the Crosswhites.

Several neighbors warned Adam that they feared that stranger would return to do more than just ask questions. A plan was struck. If Adam felt threatened, he would fire his shotgun to call for help.

That call would come in just a few weeks.

Just before dawn on January 27, 1847, four men accompanied by Sherriff Dixon began knocking on the Crosswhites’ door. When the door didn’t give, Troutman told David Giltner and the two “low-browed, truculent looking hombres***” he’d hired for this mission to get to work on the hinges.

Adam was around the back of the house feeding his chickens when he heard the door crash. He grabbed his shotgun and spied the front of his home, where his wife and children lay sleeping. After he spotted Troutman, he darted into the snow-covered woods where he stopped, pointed his weapon toward the rising sun and fired.

Within minutes, a neighbor known as “Old Auction Bell” leapt to his horse. Ringing the bell he used to call locals to the impromptu sales of trinkets called “wondoos,” he cried out to tell anyone who would listen that slave catchers were raising hell in the black quarter of the village.

White and black residents rushed to surround the Crosswhites’ home. When the crowd was large enough, Adam went inside with a few neighbors to confront the slavers.

Troutman demanded that the whole family, with exception of the child born in Michigan, return with him for delivery to their proper owner, Francis Giltner.

Adam’s neighbors made clear that they weren’t going to let that happen.

Sensing that the situation could escalate quickly, the sheriff demanded that the family come with him into town for a fair trial.

Mr. Crosswhite agreed to attend court, if the men’s authority was established. However, Mrs. Crosswhite, who was huddled in a corner with her children, refused to even consider surrender.

Outside, rumbling grew as the crowd swelled into the hundreds, despite the winter chill.

David Giltner sat down and pled with the former slaves—tearfully, according to sworn testimony—on behalf of his father. He offered a bargain. He would take only the older children and let the parents remain in Marshall with their free child.

Sarah told him that the Giltners had already taken most of her life. She intended to keep her children to care for her in her old age. Adam said he would die before he let his sons or daughters go back south without him and ordered the men out of his home.

Troutman would not budge.

More neighbors forced their way inside. One warned the Kentuckians that if they didn’t walk out of Marshall, they’d leave on their backs. Several men seconded the threat.

“What is your name?” Troutman asked the man, taking out his lawyer’s notebook.

The man responded by spelling out his name, slowly. The other men followed by announcing their name, letter-by-letter. Once each had been identified in his little book, Troutman flashed his pistol to back the throng away from the home.

The crowd was debating with the men should be tarred or feathered first when several of the town’s most prominent residents including Charles T. Gorham—a prosperous banker who had recently left the Democratic Party over slavery—arrived. Sensing a chance to take a public stand against the institution he despised, Gorham called for an impromptu town meeting where he proposed a resolution stating that the residents of Marshall would not allow the Crosswhites not be returned to Kentucky.

Armed with the screams of “Aye!” that had overwhelmed a smattering of nays, the banker volunteered to deliver the news visitors from Kentucky himself.

Troutman met him at the doorway.

“We can’t let you take them,” Gorham said. “We regard these people as free citizens and this is a free country. We don’t know slavery.”

A black man rode by on a horse, ringing a bell. Both the horse and the man quickly disappeared into the distance taking a bit of the clamor with him.

“What is your name?” the lawyer asked the banker.

After Gorham spelt his name, he tried to convince the strangers to leave the Crosswhites be.

Before impatience inside and outside the home could explode, a local official rode in from town with a warrant to arrest the Kentuckians for trespassing and brandishing weapons. The crowd was feeling mighty persuasive and several men quickly convinced Sheriff Dixon to arrest his associates so they could be brought to trial immediately.

Dixon wisely obliged.

At the hearing, Adam and Sarah Crosswhite pressed charges and testified under oath. Though the crowd roared for conviction, the judge, a well-known abolitionist, adjourned for the evening.

As night fell, cooler heads recognized that the law, as it was, was on the slavers’ side. A collection was taken up and given to the family to set off on a Detroit-bound train before dawn. The trial continued to give the family a chance to get away. By the time the Crosswhites had arrived in Buxton, Ontario, Troutman was being escorted out of Michigan with a $100 fine.

Troutman’s tales of lawless town officials aligned with fugitive slaves enraged his powerful backers. Federal legislation was proposed that would jail “abolitionist mobs.” Within weeks, a copy of the bill ended up in the hands of the publishers of Ann Arbor’s Signal of Liberty. They printed it along with mocking footnotes.

When copies of the newspaper made their way south, some Kentuckians sought revenge with kidnapping raids into Michigan. Several free blacks—some ex-slaves and even a few who had never been slaves—were dragged into bondage****. One mob of thirteen raiders from the south rode from town to town in Cass County where they were rebuffed over and over by armed white and black men united in their disgust of slavery.

Later that year, Troutman returned to Michigan to build a case against the residents of Marshall for the value of the lost slaves. He filed suit in Detroit. Using his little notebook as his key evidence, the lawyer won $4,800, the value of the lost slaves, from Charles T. Gorham, a sum that was raised from a supportive public by businessman Zachariah Chandler of Detroit. Gorham and Chandler used their popularity to help elect a slate of anti-slavery candidates from the state to the Senate and the House of Representatives, including Erastus Hussely, a stationmaster on the Underground Railroad who is credited with assisting more than a thousand slaves on their way to freedom in Canada.

If the story ended there, the Republican Party would likely have been born at some point—but years later and probably not in Michigan.

–§–

One of Francis Giltners’ neighbors in Carroll County was Henry Clay—a former Senator, Speaker of the House, Secretary of State and the founder of the Whig Party.

Clay opposed slavery, favoring reparations for slave owners and a return of those enslaved to Africa, but he—like nearly every politician of the day—recognized the constitutionality of the institution. He also shared his fellow Kentuckians’ resentment for anti-slavery “mobs” that had gathered in Michigan, Ohio and other northern states. To him, they were another threat to the federal government he’s spent his life preserving.

Following his forth and final failed run for president in 1848, the “Great Compromiser” retired from the House. He was in Kentucky long enough to get caught up in the frenzy surrounding the Crosswhite/Troutman case before being sent by the state’s legislature to back to the U.S. Senate in 1849. There he and resentments that men like Troutman nurtured would play a key role in another crisis that threatened the union.

The Missouri Compromise of 1820 required that slavery never expand into the Louisiana Purchase north of the 36° 30´ latitude line, except in the state that gave the compromise its name. The fragile balance between slave and free states established by 1820’s The Mexican-American War, which ended in 1848, resulted in southwestern territorial gains that complicated this delicate arrangement—intentionally. At least that was the contention of many anti-slavery politicians—including Henry Clay and Abraham Lincoln, then a Whig—who opposed the Democrats’ rush to war.

Proposed legislation known as the Wilmot Proviso would have resolved this issue by making illegal for the institution to spread into the newly acquired states. However, the legislation languished in Congress for years as southern states and their northern Democratic allies plotted to make the expansion of slavery a part of Manifest Destiny’s march toward the Pacific.

In the wake of President Zachary Taylor’s death in 1850 after only 16 months in office, Henry Clay seized the power vacuum to propose an omnibus bill of five separate pieces of legislation he hoped would bind the states together with an impasse that balanced the power of slave and free states. Implicit in the compromise was the assurance to the South that the Wilmot Proviso would never become law. When the bill failed, Clay vowed to pass five bills individually. Tuberculosis prevented him from doing so. In his absence, Senator Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois took over and one-by-one each bill became law, some by just a handful of votes.

The package of laws left open the possibility that Utah and New Mexico could allow slavery as California was admitted as a free state. However, its most pointed concession to the south was the new Fugitive Slave Law, which prevented Northerners from assisting freed slaves in any way whatsoever. This “Bloodhound Law” didn’t just require citizens in free states to allow the arrest of escaped slaves; it required them to aide in their capture. Any American at any time could be conscripted to hunt a fugitive slave.

To be a citizen of a nation whose founding charter sanctioned slavery had always implied a complicity in human bondage based on White Supremacism. Now, every American was just waiting for active enlistment in the cause of slavery. The law was a clear rebuke to anyone who dared to help escaped slaves—especially in Michigan.

For this despicable concession, the North was granted just four years of solace before the south and its allies threatened to throw out the Missouri Compromise again.

By 1854, the debate over the first transcontinental railroad to go Chicago hinged on settling the Nebraska territory. Industrialists demanded that it be granted statehood before they would invest the capital needed for the project.

Slavery’s best friend in the North, Senator Stephen Douglas introduced the Nebraska Act, which would split the territory into two. To win southern support, the bill allowed the white male residents of each new state a vote to determine whether they would be slave or free. This required repealing the restriction on slavery in the northern portion of the Louisiana Purchase, ending the Missouri Compromise. When southern Whigs helped pass the law in May of 1854, the party split and died immediately.

Americans opposed to expansion of slavery now recognized that any compromise made to limit the growth of the institution would only last until southern interests could find the proper lure for northern industrialists. A new party dedicated to containing slavery as a means of preserving the union was needed.

On July 6, 1854 in Jackson, Michigan, the Republican Party crafted a platform with thirteen planks, ten concerned with slavery including one that called for the repeal of the Fugitive Slave Law.

The Declaration of Rights ratified by delegates at the event began:

We believe that slavery is a violation of the rights of man — as a man — we vow at whatever expense, and publicly proclaim our determination, to oppose by all the powerful and honorable means in our power, now and henceforth, all attempts, direct and indirect, to extend slavery in this country, or to permit it to extend into any region or locality in which it does not now exist by positive low, or to admit new slave states into the Union.

Though Lincoln was elected saying that he if he could “save the Union without freeing any slave” he would, the south did not give him that choice. Southern states started seceding within weeks of his election, despite holding significant power in the Congress. The formation of the Confederate States of American proved the South had no interest in being part of a republic that even questioned the expansion of slavery.

During the war, the antipathy Lincoln felt to slavery from his childhood grew as he came into contact with black intellectuals, including Fredrick Douglas, for the first time in his life. Soon, the president’s obsession with saving the union merged with his passion for ending slavery in these United States forever.

–§–

It would be nearly impossible above from what the GOP achieved under Lincoln, and Republicans rarely did.

Once the Radical Republicans neutralized Andrew Johnson, Reconstruction was rife with good intentions and corruption. Still, true visionaries in the party brought us the 14th and 15th amendments, which ensured African Americans citizenship, establishing the right to vote for all adult males.

But in 1877, Republicans made a compromise that shaped the political dynamics until the 1960s. In order to swing the presidency to Rutherford B. Hayes after the most disputed election in American history, Republicans agreed to a demand from the Democrats, who were then still very much the bad guys in our story, to withdraw the remaining federal troops from the South. Democrats swept into power in Florida, Louisiana and South Carolina. Jim Crow laws were enacted to crush any hope of a populist movement uniting poor whites and blacks. The principle of “separate but equal” spread and the right to vote for Southern males—and females after 1920—died.

Conservatives would like you to believe history ended there—and many conservatives would have been happy if it had. But our politics were reshaped first when Harry Truman made civil rights part of his 1948 campaign then irrevocably when the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 became law .

Though a majority of Republicans voted for both bills, the right’s “Southern Strategy”–forged when Richard Nixon promised Southern Democrat-turned-Southern Republican Strom Thurmond that he would stonewall desegregation–played on racial resentments to give Republicans a governing majority that saw them win the White House five out of six times between 1968 and 1988.

Democrats tried to neutralize their weakness by abetting the so-called War on Drugs, which has led to a 790 percent increase in the federal prison population since 1980, with blacks and Latinos disportionately imprisoned for drug crimes and serving longer sentences, though they do not use or sell drugs at any significantly higher rate.

–§–

You know that Dr. Martin Luther King said that, “Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere.”

When the Crosswhites’ neighbors rose to their neighbors’ defense, they weren’t trying to change the country. Given the choice between abetting or rejecting a great wrong, they could do nothing else.

After the Civil War, Adam and Sarah brought their family back to Marshall, where they lay today, among friends.

* Headwear imagined by the author.

** This historical event has been dramatized based on court transcripts and History of Calhoun County, Michigan; a narrative account of its historical progress, its people, and its principal interests by Washington Gardner.

*** According to William W. Hobart.

**** See The Underground Railroad in Michigan By Carol E. Mull