Michigan Radio’s Lester Graham has a great piece out this week titled, “More and better jobs?” that takes a balanced look at Rick Snyder’s claims about the rebounding of Michigan’s and his role in it. What Graham shows is that much of the job growth in Michigan is due to the rising national economy and, just as importantly, efforts taken by his predecessor, Jennifer Granholm:

Michigan Radio’s Lester Graham has a great piece out this week titled, “More and better jobs?” that takes a balanced look at Rick Snyder’s claims about the rebounding of Michigan’s and his role in it. What Graham shows is that much of the job growth in Michigan is due to the rising national economy and, just as importantly, efforts taken by his predecessor, Jennifer Granholm:

Governor Snyder…takes credit for an increase in employment that actually began under his predecessor, Jennifer Granholm. The annual average employment hit bottom in 2009 and began improving in 2010, during Granholm’s final year in office.The job growth trend began before Snyder was elected. There are now 289,000 more people working than in the depths of the recession.

As we’ve reported previously, Don Grimes, an economist at the University of Michigan, says once you factor out the effects of the improving national economy and the resurgence of the auto industry, there’s not much credit for the governor to take.

“[Out of the 300,000 private sector jobs that Snyder is taking credit for,] you’re probably looking at about a 10,000 to 15,000 job gain each year that cannot be explained by the national economic growth or cannot be explained by the strong performance of the auto industry. And that’s sort of a maximum that Governor Snyder can be really claiming, in the nature of 10,000 to 15,000 jobs,” Grimes said. […]

One of the benchmarks to determine whether there are better jobs is the median household income. Michigan, like much of the nation, has lost ground. Adjusted for 2013 dollars, the median household income in Michigan has fallen from a high of $56,204 in 2006 to $48,801 in 2013. That’s a loss of $7,403. While the median household income did begin to increase in the first two years of the Snyder administration, last year it lost ground, falling to its lowest level in more than decade. The national median household income for 2013 was $52,250.

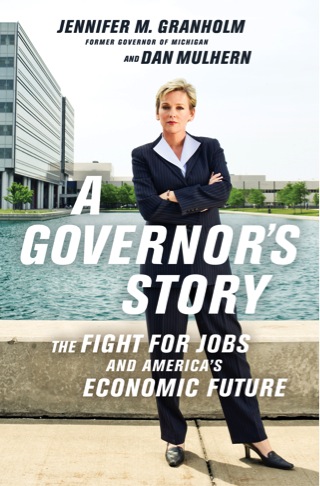

With the election approaching and Gov. Snyder’s efforts to take credit for the successes of others in terms of Michigan’s recovery, I thought it would be useful to repost a review of Jennifer Granholm and Dan Mulhern’s book A Governor’s Story – The Fight for Jobs and America’s Economic Future that I did a few years ago. When Michigan Republicans giddily refer to Granholm’s eight years in office as Michigan’s “lost decade”, what they don’t like to admit is that, to the extent that Michigan is rebounding, much of the credit for that goes to Granholm and the groundwork that her administration laid before she left office. I have little patience for those who blame Granholm for the impact on Michigan of the collapse of the national economy. In truth, as bad as things were in Michigan, they would have been catastrophically worse without the efforts of her and her administration, working in concert with the Obama administration. Granholm and Mulhern’s book tells a story that Republicans don’t want you to hear, particularly since they stood in the way of much of what Granholm tried to do, making things even more difficult.

Jennifer Granholm and former First Gentleman Dan Mulhern’s new book, A Governor’s Story – The Fight for Jobs and America’s Economic Future is an important contribution to the conversation and debate that is occurring right now over our economic path forward as a country. The question is, will the rest of the country learn from Michigan’s experience?

A Governor’s Story is a first-person account told in Granholm’s voice. However, as is made clear from the start, it is a collaborative effort between her and Mulhern. The book tells three different stories. First, it is a history lesson about the impact on Michigan of the Great Recession of this decade, a state with seven times more manufacturing jobs per capita than any other state. Second, it is a behind-the-scenes look at how states are run at the highest level. It shows the tightrope walking that must be done, the non-stop compromising, cajoling and effort that it takes to get things done, particularly during the time when Granholm was governor and the state legislature was either partially or entirely controlled by Republicans. Finally, it is an important textbook describing the successes and failures Michigan experienced as it dealt with the economic collapse—including an entire chapter devoted to outlining concrete things that can be done at the federal level to help our country out of the recession, all based on lessons painfully learned in Michigan.

A Governor’s Story is a first-person account told in Granholm’s voice. However, as is made clear from the start, it is a collaborative effort between her and Mulhern. The book tells three different stories. First, it is a history lesson about the impact on Michigan of the Great Recession of this decade, a state with seven times more manufacturing jobs per capita than any other state. Second, it is a behind-the-scenes look at how states are run at the highest level. It shows the tightrope walking that must be done, the non-stop compromising, cajoling and effort that it takes to get things done, particularly during the time when Granholm was governor and the state legislature was either partially or entirely controlled by Republicans. Finally, it is an important textbook describing the successes and failures Michigan experienced as it dealt with the economic collapse—including an entire chapter devoted to outlining concrete things that can be done at the federal level to help our country out of the recession, all based on lessons painfully learned in Michigan.

THE POLITICAL& ECONOMIC HISTORY OF MICHIGAN — 2003-2011

When Granholm took over as governor, she immediately faced a plethora of challenges. John Engler had depleted the state’s large rainy day fund to mask the devastation he had done to the state budget. Our roads and other infrastructure were in terrible shape, and the state faced a massive budget deficit that would only get worse as other actions taken by the Engler administration phased in. Shortly after she took office there were riots in Benton Harbor, a massive blackout that took down much of the northeastern part of the U.S., and the near-bankruptcy of the Detroit Medical Center, the state’s largest health care system. As the book points out, all of these crises and their impacts could be traced back to a lack of investment by previous administrations.

As is typical, Michigan, with its large manufacturing base, was the first to feel the impacts of the impending economic crisis. An ever-tightening state budget was further strained by diminishing tax revenues. As her first term was ending, many of Granholm’s campaign promises had not been attended to, mainly because so much of her time was spent in crisis-management mode. As she moved into her second term, things only got worse. As someone who pays attention to politics and the news and who has lived in Michigan his whole life, I was surprised to realize how bad things were during that time. It made me realize that I, like many others, never really faced the reality of how desperate our situation was. A timeline in the beginning of the book tells the tale in stark and frightening terms. One particular part of the book dramatically tells the tale:

On December 2, 2008, the November sales numbers were released. They were shocking. GM sales had plummeted 41.3 percent; the company needed $18 billion in loans, $4 billion just to survive the rest of the year. Chrysler reported a 47 percent sales drop; it was seeking a $7 billion bridge loan to stay afloat. Ford reported a 31 percent drop; it, too, was hoping for government aid.The next day, at a meeting of governors in Philadelphia convened by the president-elect, I sat next to Governor Janet Napolitano, who would soon be secretary of homeland security.

“How’s it going?” she asked.

“Candidly, we’re drowning. If Congress doesn’t give loans to the auto industry, I can’t tell you what it will be like. Janet,” I asked on a whim, “how many WARN Act notices do you think you’ve received in Arizona?” The federal WARN Act requires a company to notify a governor when it intends to do a “mass layoff”, defined as fifty or more workers. She looked at me curiously.

“I don’t know, maybe a handful since I’ve been governor,” she said. “Why? How many have you received?”

“Fifty-five in the past thirty days,” I answered.

In the next six months, Granholm would receive another 316 WARN notices. Hotlines set up to help the unemployed were taking 800,000 calls per day.

Despite this economic catastrophe, the Granholm administration never relented. Their outreach to other countries brought in 48 new companies, $2 billion in new investments and 20,000 new jobs. Over 10,000 state employee jobs were eliminated and $600 million in state worker concessions were negotiated. During her tenure, no less than 99 business tax credits/cuts were enacted and 17 different individual tax breaks. The personal tax burden in Michigan went from 12th highest in 2000 to 39th by 2008.

Perhaps most frustrating for Granholm was the fact that Michiganders during this time continued to believe that state government was bloated and that she was raising their taxes. The lack of acknowledgement or awareness of the reality of Michigan’s plight by its own citizens is a common theme in A Governor’s Story.

BEHIND THE SCENES: A FIERCE ADVOCATE FOR MICHIGAN

One of the recurring themes in A Governor’s Story is the energy and determination that Granholm brought to the governor’s office. During her time in office she traveled the state, the country and the world pursuing new opportunities. She worked with other governors to share best practices and maintained a close relationship with the Obama administration as it worked to pull the country back from the economic precipice. Her insistence on the importance of education, diversification and investment in new industries like green energy was in nearly perfect unison with Barack Obama’s own philosophy. But, even while she was working with the country’s leaders, she was also grounded in the reality of Michigan’s hardest hit citizens. At one point when things were at their lowest ebb, the Governor went to a Constituent Services office where state workers were fielding calls from out-of-work Michiganders to thank them for doing a very difficult job.

I had a half-hour available, so I went down to the floor below to thank the beleaguered team answering the phones. I touched shoulders and offered thanks between calls. Then, in the spirit of teamwork, I sat at an empty cubicle and picked up the ringing phone.“Governor Granholm’s office, how can I help you?” I mimicked those around me.

“That stupid governor!” the caller burst out, not realizing who had answered the phone. “She needs to quit talking to Obama and order those plants to stay open!”

“She doesn’t have the power to do that, ma’am,” I began, as politely as possible.

“Well, if she doesn’t have the power, then what good is she anyway?” The woman slammed the phone in my ear.

The book recounts in great detail the day-to-day, hands-on approach taken by Granholm and her staff to work with the Detroit Three auto companies and other major employers to help stave off complete failure. Even as the namesake of Comerica Park in Detroit where the Tigers play baseball left the state to set up shop in Texas, Granholm’s team was intimately involved in trying to soften the blow to Michigan workers.

MICHIGAN AS AMERICA’S ECONOMIC LABORATORY— LESSONS LEARNED, LESSONS TAUGHT

Perhaps the most important aspect of A Governor’s Story is that Granholm and Mulhern have some critical observations and recommendations for the country based on failures and successes in our state. The final chapter is devoted to nine specific recommendations.

In their suggestions, Granholm and Mulhern show that a laissez-faire, let-the-market-lead approach is devastating in a time economic crisis. We aren’t just competing among our own domestic companies. Even at the local level, companies are competing against companies in other countries, some a half a world away. And these foreign competitors typically enjoy a business climate helped by government assistance, universal health care (which relieves them of the health care burden borne by U.S. companies), and inexpensive labor. We need to help our own companies compete on that global playing field. “Why do Americans say they hate an active government, then get mad when government does nothing while their jobs disappear?” Granholm asks. “How can we compete against rivals like these when we insist on government passivity?”

Granholm and Mulhern also advocate strategic investing in regionally important and otherwise crucial industries. While conservatives rail against governments “picking losers and winners,” Granholm and Mulhern point out that businesses do this every day in our country.

“Businesses do it all the time,” she writes. “They invest to capitalize on their strengths and their need. They choose based upon their company’s strategic direction. What’s the problem with the U.S. government being smart and strategic, too?” They also point out that, while they decry “picking winners & losers,” conservative governors across the country are doing this very thing to bring business to their states even as they condemn doing it at the national level.

One of the crucial lessons Granholm and Mulhern convey is that tax cuts are decidedly not the sole answer to today’s economic challenges. Despite the Granholm administration’s 99 business tax incentives and nearly Pyrrhic efforts to keep companies like Electrolux in our state, at the end of the day, Michigan’s tax rate is not the cause of our shrinking manufacturing base. High taxes aren’t driving companies away. Infinitesimal wages in other countries are drawing companies away. “To be clear,” she writes, “the cuts did create many jobs – but not necessarily in America. Michigan’s tax cuts, and those championed by President George Bush at the national level, freed up capital for investors and companies. But much of that capital was being invested far from Michigan and away from our country altogether.” We must create an environment where companies want to come back — a state full of highly-educated, talented workers and cities that attract these people, according to Granholm and Mulhern.

Finally, Granholm and Mulhern extol the vital role played by education. The Granholm administration’s No Worker Left Behind program is a model for the country. By last year, because of this program, Michigan had displaced workers being retrained at a level four times the national average, an effort that is clearly beginning to pay dividends.

FINAL THOUGHTS

There are, of course, some revelations in A Governor’s Story. For example, Granholm reveals that their Catholic bishop met with them privately to inform her that, because she was a pro-choice politician, she was not worthy to receive communion. She tells how Andy Dillon flaked out in a crucial budget negotiation, ruining weeks of effort, rather than helping show a united front. In the book, we learn that Granholm was uncertain about running for a second term and suggested that Michigan Senator Carl Levin should be recruited.

Granholm also laments the state of politics in America today where politicians are punished for being honest about what is needed to make our country successful. During the 2006 campaign, she and Dick DeVos did not “tell people the things that deep down [they] both knew to be true” about the future of Michigan and what it would take to turn our state around. “American political campaigns don’t reward that sort of thoughtful analysis,” she writes. “If anything, they punish those who attempt it.”

An interesting piece in light of the current race for the Republican nomination are the things Republicans said about the so-called “bailout” of the Detroit Three automakers. Granholm and Mulhern remind us, for example, that Mitt Romney wrote a New York Times op-ed suggesting that the companies not be given assistance. Jon Huntsman, also a contender, called the loans given to these companies “a big mistake”. Tim Pawlenty, who was once in the running for the GOP nod, said saving the auto companies and other Obama administration efforts would make America look “like some sort of republic from South America circa 1970s”. Finally, Newt Gingrich, still in the race, said that the saving of the automotive industry was evidence that President Obama is “the most radical president in American history.” All of these men have been proven quite wrong in their assessment of the wisdom of saving the Detroit Three and tens of thousands of Americans across the country whose jobs are in some way related to vehicle manufacture are thrilled they were ignored.

One piece I felt was missing from A Governor’s Story was the role of Lt. Governor John Cherry. Although he is mentioned a couple of times in passing, it’s hard to imagine that he was Lt. Governor for eight years without playing a more prominent role than is described in the book. Other members of Granholm’s staff are mentioned far more frequently. The book also downplays much of the vicious political rancor that went on during her administration. The division is there, for sure, but my memories of the game-playing and downright ugly political maneuvering that played out on the news and in the media are actually much more colorful than this account.

The parallels between Jennifer Granholm’s time in office and what Barack Obama is confronting in his first term as president are unmistakable. Both came to office facing frightening economic challenges but with bold ideas for change. Both faced stiff headwinds from ideologically-motivated opponents intent on thwarting everything they attempted. Both are, frankly, blamed for things that were beyond their control. As Granholm and Mulhern exit stage left, they are leaving us with a thoughtful, well-informed and honest account of what went right, what went wrong and what lessons we can learn from Michigan, a state Granholm called a “laboratory of democracy” in a New York Times interview this week. Whether you are a Democrat or Republican, conservative or liberal or independent, A Governor’s Story teaches important lessons. Let’s hope our leaders are willing to learn from them.

Photo by Anne C. Savage.