This guest post comes from Sean McElwee — a research associate at Demos and an excellent follow on Twitter.

If you haven’t already, check out Sean’s work on Salon, Rolling Stone, his own blog and various other publications. You’ll see that he has a gift for lucidity and a healthy obsession with improving our democracy by increasing voting, dispelling economic myths and decreasing the influence of big money.

This post draws on his research into voter turnout with an focus on the state of Michigan. He identifies where we’re succeeding and what needs to be done to drown out the distorting effects of big money and gerrymandering in our state. Like most of the country, this state would be in much better shape if everyone voted.

You’ll only see these particular findings on Eclectablog and we thank Sean for this and all the essential work that he and Demos do.

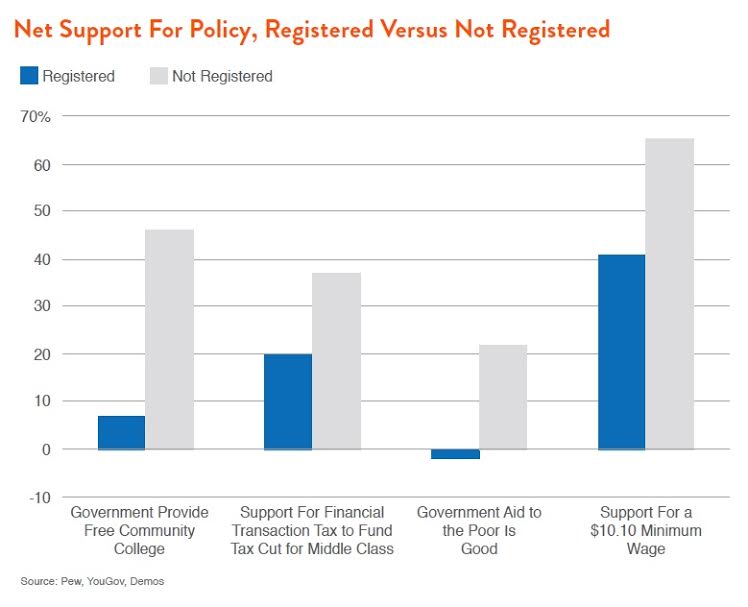

My recent explainer “Why Voting Matters: Large Disparities in Turnout Benefit the Donor Class” shows why voter turnout matters: politicians respond to voters more than nonvoters, and nonvoters have distinct preferences from voters. Non-voters tend to be younger, poorer and more non-White than voters, and also more progressive. One of the key charts in my report (see below) shows that on key issues, the non-registered population is far more progressive than the registered population. Using a wide political science literature that draws from state level, historical and international studies, I show that one way to bring around more progressive policies is to boost voter turnout. Though the report doesn’t focus in-depth on Michigan, I’ve performed an analysis of the Census Bureau turnout data that provide some key lessons.

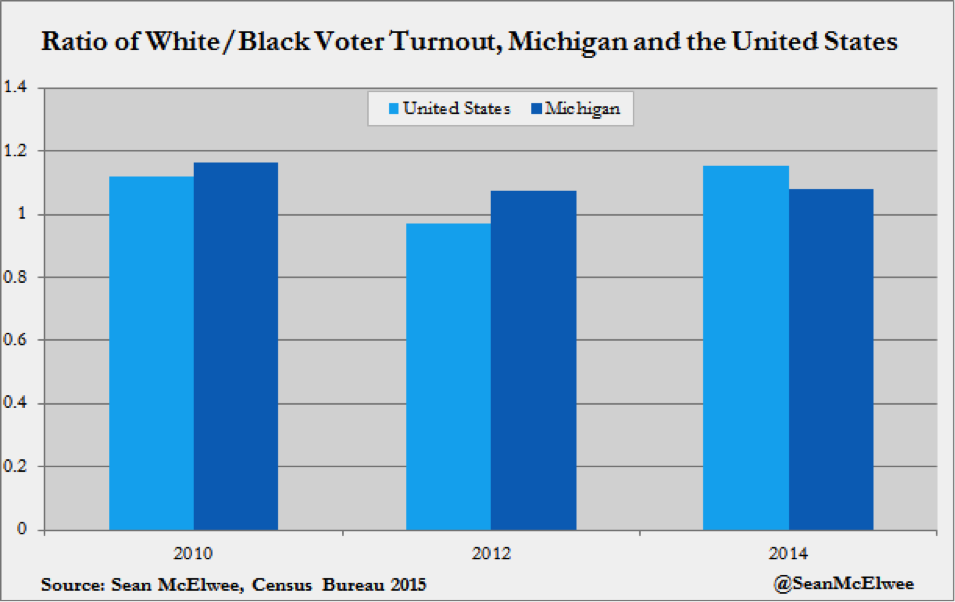

In 2014, Census data suggest that turnout nationally was 41.9%, but Michigan had higher turnout, 47%. However, turnout isn’t the same across all groups, and we know that groups that don’t vote get less representation. So who is losing out? While the margin of error for turnout among Hispanics and Asians were prohibitively high at the state level (my report includes national-level data), I was able to compare turnout among African-Americans and whites in Michigan. As the chart below shows, the ratio of turnout between whites and Blacks (1 indicates parity, below 1 indicates higher turnout among Blacks and above 1 indicates turnout biased towards whites) has improved in Michigan. In 2014, Michigan outperformed other states, with slightly more equal turnout, while in 2010 and 2012 turnout was more biased than nationally.

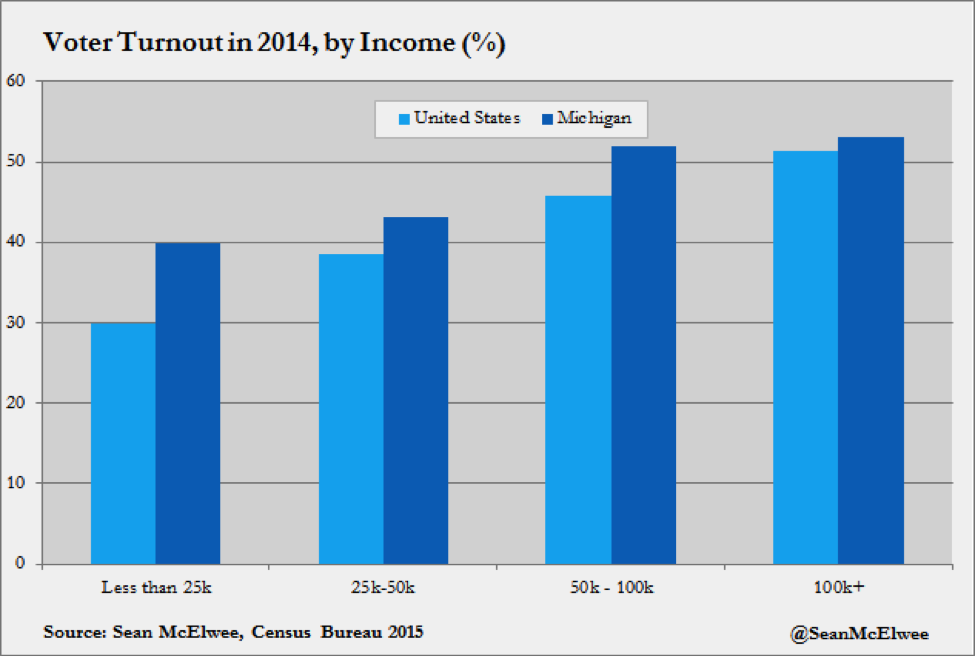

Census data indicate that Michigan has performed well in terms of class bias of voter turnout. As the chart directly below shows, voter turnout in Michigan was higher than within the national overall in 2014. Particularly impressive is voter turnout among those earning less than $25,000 who voted a rate 10 points higher in Michigan than nationally.

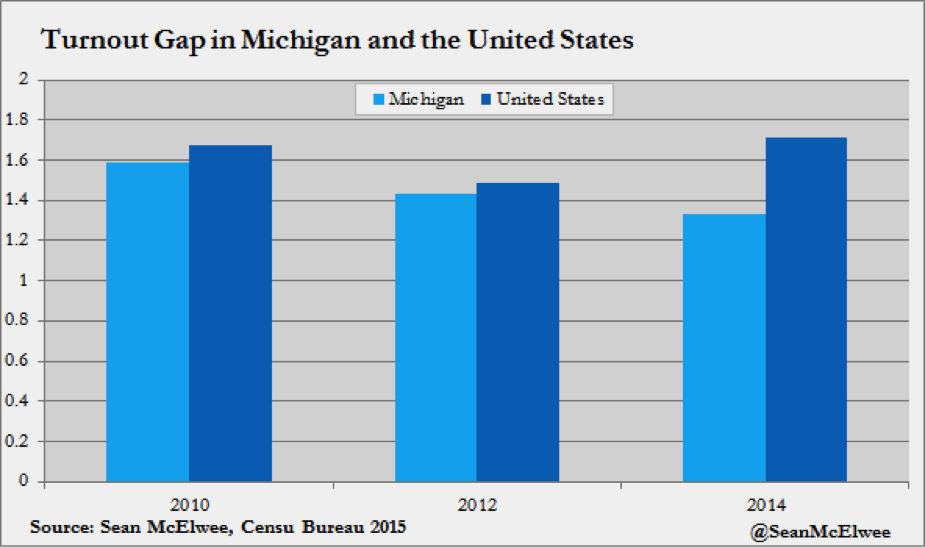

To compare turnout patterns over time, I used a relatively simple measure of class bias, the turnout of the wealthy (those earning over $100,000) divided by the turnout of low-income people (those earning below $25,000). This gives a simple ratio of turnout between the rich and poor, if the number is 1, turnout is equal, if it’s below 1, the poor are more likely to vote (no state has this scenario) and if it’s higher, the rich are more likely to vote. In Michigan, the ratio has reduced over the last three elections, and is now quite lower than the gap across the United States.

Why? A likely reason is that the registration gap in Michigan is far lower than in the nation as a whole, partially because registration rates are so much higher (higher registration and turnout tend to reduce bias, since the marginal voter tends to be poorer than the median). Michigan has nearly reached registration parity; in 2014, 69% of those earning less than $25,000 were registered in Michigan (compared to 54% nationally) and 74% of those earning more than $100,000 were registered (compared with 73% nationally).

One reason for high levels of registration in Michigan may be its incredibly effective implementation of the “Motor Voter” section of the National Voter Registration Act, which requires states to offer citizens the chance to register when they use the DMV. Such registrations account for 77% of registration forms received in 2012 – 2014 period. As Stuart Naifeh reported in a recent Demos report, Driving the Vote:

Michigan’s implementation of Section 5 of the NVRA is distinctive in at least two key ways. First, the Secretary of State is responsible for both elections and licensing drivers. Second, Michigan requires voters to use the same residence address for both driver’s license and voter registration. Together, these features of Michigan law have allowed Michigan to implement a system of streamlined registration that is effectively permanent, at least for voters who hold a driver’s license or state ID card.

Naifeh writes, ”Among all states, Michigan has the highest DMV voter registration rate.” More than half of transactions at the DMV in Michigan result in the individual becoming registered to vote, a stunning rate.

Research suggests that reforms like Motor Voter and Same-Day Registration that boost registration tend to reduce class bias, as do competitive elections. The presence of strong unions also serves to modestly reduce bias (Michigan has the country’s 11th highest unionization rate, though the passage of right-to-work has pushed this number downward). Michigan could further reduce class bias by passing a Same-Day Registration bill, adding pre-registration for youth and abolishing its vote ID requirement (research suggests voter ID laws increase the class bias of turnout). Simply because Michigan has high voter turnout doesn’t mean there’s not more to be done: in 2014, the turnout rate among those under 30 earning less than $30,000 was 17%. Among those over 50 earning more than $100,000 it was 67%. When a policymaker is trying to decide whether to cut taxes on the rich or use the money to invest in higher education, that’s going to matter.