The following guest post was written by Nick Krieger, an attorney and former clerk in the Court of Appeals. Follow him on Twitter at @nckrieger. His essay is published here with permission.

Enjoy.

“Republican senators have dishonored the original meaning of the United States Constitution”

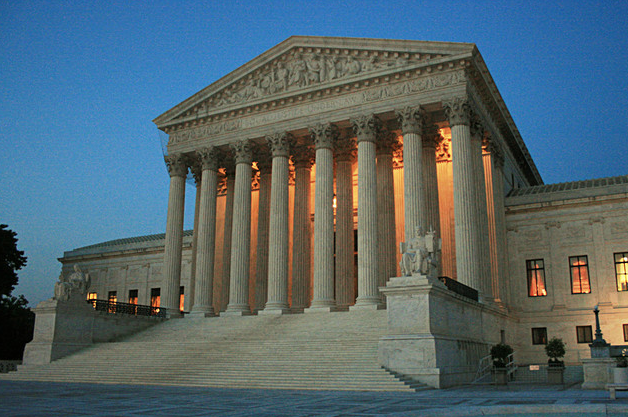

We hear it almost every day. Like a broken record, the Republicans in the United States Senate repeat the incessant refrain that they will not schedule hearings or hold a vote on President Obama’s forthcoming nominee to replace the late Justice Antonin Scalia on the United States Supreme Court. Indeed, this particular Republican talking point has taken on a life of its own, gaining increasing popularity on social media platforms like Twitter with the hashtag #NoHearingsNoVotes.

But let’s pause the insanity for a moment and delve deeper into the meat of the controversy.

As is true of most disputes between different branches of government, this controversy begins with the text of the United States Constitution itself. The Appointments Clause of Article II, section 2 provides in relevant part that the President “shall nominate, and by and with the Advice and Consent of the Senate, shall appoint . . . Judges of the supreme Court . . . .” It is beyond dispute that the word “shall” is a term of mandate, denoting a compulsory requirement — just as it was when the Constitution was drafted in 1787. Substituting the term “must” in place of the word “shall,” the meaning of the Appointments Clause becomes more apparent: The President must nominate, and by and with the advice and consent of the Senate must appoint Justices of the Supreme Court.

There are other clear indications that the Framers intended this language to create a mandatory obligation as well. Look no further than the Treaties Clause of Article II, section 2, which states that the President “shall have Power, by and with the Advice and Consent of the Senate, to make treaties, provided two thirds of the Senators present concur.” The Treaties Clause—the only other clause in the United States Constitution to mention the advice and consent of the Senate — is particularly useful in interpreting the Appointments Clause. It does not require the President to make treaties, but provides only that the President has the power to make them. This is classic language of discretion. It confers upon the President the power to enter into treaties, but does not compel him to do so. If the Framers had intended to make presidential nominations optional rather than mandatory, they could have simply duplicated the discretionary language of the Treaties Clause.

Thus, when you hear Senate Republicans complaining that no one should be nominated to fill the Supreme Court vacancy until after the next President is inaugurated on January 20, 2017, remember that it is President Obama’s constitutional obligation to nominate someone to fill the seat formerly occupied by Justice Scalia. Quite simply, the President has no choice in the matter—he is constitutionally required to choose a nominee and forward that individual’s name to the Senate for consideration.

Republicans also argue that the Senate has no duty to schedule hearings or hold a vote on a presidential nominee. Albeit more complicated, this argument is belied by the text of the Constitution as well.

The Appointments Clause does not merely state that the President must nominate Supreme Court justices. It also says that the President must appoint Supreme Court justices by and with the advice and consent of the Senate. What does this mean?

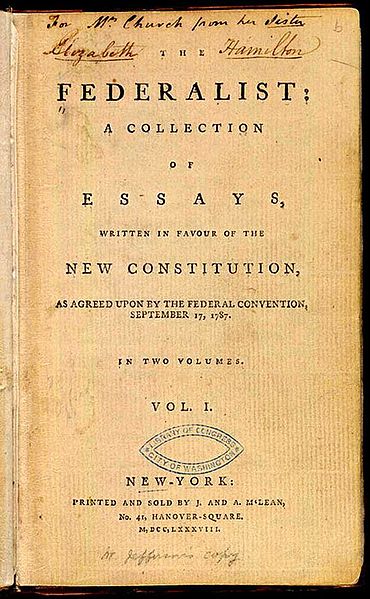

The most compelling understanding of the Appointments Clause is that advanced by Alexander Hamilton in The Federalist. You will recall from civics class that The Federalist (also referred to as the Federalist Papers) is a collection of 85 essays written anonymously by Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and John Jay in 1787 and 1788 to promote the ratification of the proposed United States Constitution. The essays form a point-by-point analysis of the various sections of the proposed Constitution, and are considered to be valuable evidence of the Constitution’s original meaning at the time of ratification.

The most compelling understanding of the Appointments Clause is that advanced by Alexander Hamilton in The Federalist. You will recall from civics class that The Federalist (also referred to as the Federalist Papers) is a collection of 85 essays written anonymously by Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and John Jay in 1787 and 1788 to promote the ratification of the proposed United States Constitution. The essays form a point-by-point analysis of the various sections of the proposed Constitution, and are considered to be valuable evidence of the Constitution’s original meaning at the time of ratification.

In The Federalist No. 66, Hamilton envisioned that the Senate would hold a vote with respect to each nominee put forward by the President — either approving or rejecting the individual nominated for each position. As Hamilton wrote, “[The senators] may defeat one choice of the Executive, and oblige him to make another; but they cannot themselves choose — they can only ratify or reject the choice of the President.” Hamilton expanded on the advice-and-consent role in The Federalist No. 76, explaining that the Senate’s only recourse when faced with an unacceptable nominee would be to hold a vote and reject the nomination, thereby requiring the President to nominate a different individual. Through this process, Hamilton observed, the President would ultimately find a mutually satisfactory nominee — someone, even if not the President’s first choice, who would be acceptable to both the President and a majority of the senators. At the same time, Hamilton also cautioned that the Senate should be wary of rejecting the President’s first choice. As Hamilton explained, senators who vote to reject a presidential nominee can never know for sure whether the next person nominated to fill the position might be even less acceptable.

The Framers did not merely intend for the Senate to provide an up-or-down vote on every nominee; they also intended that the Senate would exercise this advice-and-consent function without delay. Consider the purpose underlying the Recess Appointments Clause of Article II, section 2. At the time of ratification, the United States Senate took more and longer recesses than it does today. If the Framers had intended to allow federal positions to remain vacant for long periods, they would not have included the Recess Appointments Clause. After all, had the clause not been included, the President would have been required to wait for the Senate to reconvene — possibly months later — before making any appointments. The fact that the Framers included the Recess Appointments Clause is strong evidence of their intent to ensure that federal positions, like judgeships, would be promptly filled to facilitate the seamless continuation of government upon the death, removal, or resignation of an incumbent officeholder. The Framers would be aghast at the thought of a system wherein the Senate, while in session, could simply refuse to consider a nominee put forward by the President.

The Framers did not merely intend for the Senate to provide an up-or-down vote on every nominee; they also intended that the Senate would exercise this advice-and-consent function without delay. Consider the purpose underlying the Recess Appointments Clause of Article II, section 2. At the time of ratification, the United States Senate took more and longer recesses than it does today. If the Framers had intended to allow federal positions to remain vacant for long periods, they would not have included the Recess Appointments Clause. After all, had the clause not been included, the President would have been required to wait for the Senate to reconvene — possibly months later — before making any appointments. The fact that the Framers included the Recess Appointments Clause is strong evidence of their intent to ensure that federal positions, like judgeships, would be promptly filled to facilitate the seamless continuation of government upon the death, removal, or resignation of an incumbent officeholder. The Framers would be aghast at the thought of a system wherein the Senate, while in session, could simply refuse to consider a nominee put forward by the President.

It is important to remember that the Senate Republicans who are now insisting on an incorrect, confused reading of the Appointments Clause are the very same senators who championed an erroneous interpretation of the Treaties Clause last year. Remember the now-infamous letter to Iran, in which 47 Republican senators asserted that “[i]n the case of a treaty, the Senate must ratify it by a two-thirds vote”? This fundamental misunderstanding of the Senate’s constitutional role was rather astounding, especially given that attorneys such as Senators Ted Cruz and Marco Rubio signed the Iran missive.

While it might seem like an exercise in semantics, the point is well established: The Senate does not make or even ratify treaties. Instead, it provides “advice and consent” to the President during the treaty-making process. The power to make a treaty belongs to the President alone. Thereafter, if two-thirds of the senators give their consent, the President may finalize or ratify the treaty, thereby making it the supreme law of the land.

The same misunderstanding of the Senate’s advice-and-consent role has infected the current debate. The Senate Republicans — many of whom disingenuously claim to follow an originalist interpretation of the Constitution — now wish to impermissibly expand the meaning of “advice and consent” beyond anything the Framers ever imagined. But, just like the advice and consent that is essential to the treaty-making process, the advice and consent essential to the appointment process is restricted in scope — it does not imbue the Senate with its own plenary authority over appointments, but only with the responsibility to affirm or reject the President’s personal choice.

The constitutional text and weight of primary authority compel but one conclusion: The Framers intended that the Senate would, without unnecessary delay, provide an up-or-down vote for each nominee put forward by the President. By announcing that they will not schedule hearings or hold a vote on President Obama’s nominee for the Supreme Court, Republican senators have dishonored the original meaning of the United States Constitution. The choice of a nominee belongs to the President alone, and the Senate is obligated to promptly approve or reject each nominee. If the senators find President Obama’s nominee to be unacceptable for any reason, they may vote to reject him or her. But the President must then forward the name of a new nominee, and the process must start afresh — continuing in the same fashion until a nominee is eventually approved by the Senate and appointed. That’s the exactly how our Constitution was designed to work, and it demands nothing less.

[CC photo credit: Mark Nester | Flickr]