However you might define him, this man is who he is.

This is part of a story series about the lives of transgender people. Read the introduction here.

Codie Stone isn’t big on labels. He accepts them as a fact of life in our society. But for Stone, what matters most is living his life authentically. He just wants to be who he is.

Codie Stone isn’t big on labels. He accepts them as a fact of life in our society. But for Stone, what matters most is living his life authentically. He just wants to be who he is.

Stone’s gender identity wasn’t always clear to him. In fact, he says he didn’t have the “classic transgender” experience of knowing since he was a kid that the female gender he was assigned at birth didn’t reflect his true self. Instead, the 31-year-old Stone says, his transition happened over many years.

It was a very slow, gradual understanding that people were living their lives differently and that I had a lot more options than I thought I did.

He remembers crying when his mother tried to make him wear dresses. “There were a lot of times growing up when I wanted to express myself differently — I cut my hair short even though my mother didn’t like it and I got in trouble,” he says. “But it wasn’t until I was in college that I let myself consciously think about the fact that I could be different from other people.”

Stone had a turbulent childhood, growing up with an abusive stepfather. Living in a conservative part of Ohio, no one pushed him to talk about sexuality or gender, for which Stone is grateful.

“I ignored everything related to sexuality and things that didn’t feel ‘normal’ about me,” he says. “It was not a safe place to explore things like that.”

In college, Stone began taking classes in gender studies, sexuality, women’s studies and sociology, which ultimately led to multiple degrees, including bachelor’s and master’s degrees in sociology. As he began meeting new people who were open to different ideas, his view of the world expanded.

I met my first out lesbian and that was exciting to me. I came out as bisexual, and then as a lesbian, after I met a women and started dating her. I had never thought of myself as anything but a woman, and here I was dating a woman. It was an awkward thing to figure out and tell people, but it seemed to make the most sense. Here was the label that fit me.

Stone admits that as an adult, he’s always had a masculine expression, and when he identified as a lesbian he was a butch lesbian. In college, though, he really began delving into gender roles.

“I thought, ‘It’s okay, I’m just a different kind of woman,’ and I could live with myself that way,” he says. “But as I learned there were people who were doing things to live in a more comfortable way, I didn’t have to be that woman. I’m very pro-woman, but I could be more comfortable in my own skin.”

At that point, Stone began thinking of himself as genderqueer, which is an umbrella term for people whose gender identity doesn’t fit within the constraints of the binary of female and male.

It wasn’t long before he began meeting some transgender men. Although Stone didn’t necessarily relate to most of them — “they were into hyper-masculine stuff that’s never been me,” he says — it opened his eyes to the existence of transgender people.

Later, when Stone and his partner, Lisa, moved to Kalamazoo, his perspective was broadened even more while volunteering to help pass the city’s non-discrimination ordinance in 2009.

That was where I met the first trans guy I ever felt a connection with. He asked me what pronouns I used and I didn’t know — no one had ever asked me. I couldn’t give him an answer.

It was the first time I knew I had an option — I could make a choice, I didn’t have to say the thing everyone expected me to say, the thing that didn’t make me feel like myself. At first I chickened out and said I didn’t care about pronouns, but over time I started using male pronouns. It felt good and right.

And it got Stone thinking. During that campaign he realized that living and expressing a male gender identity was important to him. For Stone, that meant beginning hormone replacement therapy with testosterone.

I was very into passing as male and being seen as male by others. As I’ve been on T for the last six years, I find myself less into identifying in that masculine male-ness. I feel like I just do things I like to do, and society says ‘those are male things’ or ‘those are female things.’ I’m not a fan of the whole mainstream male culture, so it’s hard for me to feel a connection with everything I associate with that. I’m just trying to be me, and if people ask for a label I’ll give them whatever is easiest to get them through conversations.

Personally, Stone identifies as trans masculine genderqueer. But he admits that he’ll sometime gauge the situation and present himself in a way that makes the most sense. For example, there are times he feels safer relying on his ability to be seen as a cisgender male — someone who was assigned male at birth.

“I rely on that privilege for safety if I need to,” he says.

Acknowledging that privilege and the danger many transgender people face being “outed” against their will is one reason Stone signed on to be a named plaintiff in lawsuit filed by the American Civil Liberties Union and ACLU of Michigan against the Michigan Secretary of State. The lawsuit is challenging a department policy that makes it impossible for many transgender individuals to correct the gender on their driver’s licenses and other forms of identification, something that’s already easily done on federal documents such as passports. The case is back in court this week.

Because Stone was born in Ohio, a state that doesn’t allow people to change their birth certificates, Michigan’s current law would mean he could never change the gender marker on his driver’s license.

I don’t care about the label, but I know the State of Michigan cares about the label. I’d rather have an M on my driver’s license if I get pulled over. I have a beard. I don’t look very feminine. I don’t know what would happen if I got pulled over. But given the option, I’d like to get an M on my driver’s license to better reflect how society sees me and how I choose to express myself.

And I have a certain privilege that many other transgender people don’t, because they might not look traditionally cisgender. I have the opportunity to safely put myself out there to help the community, so I want to do that.

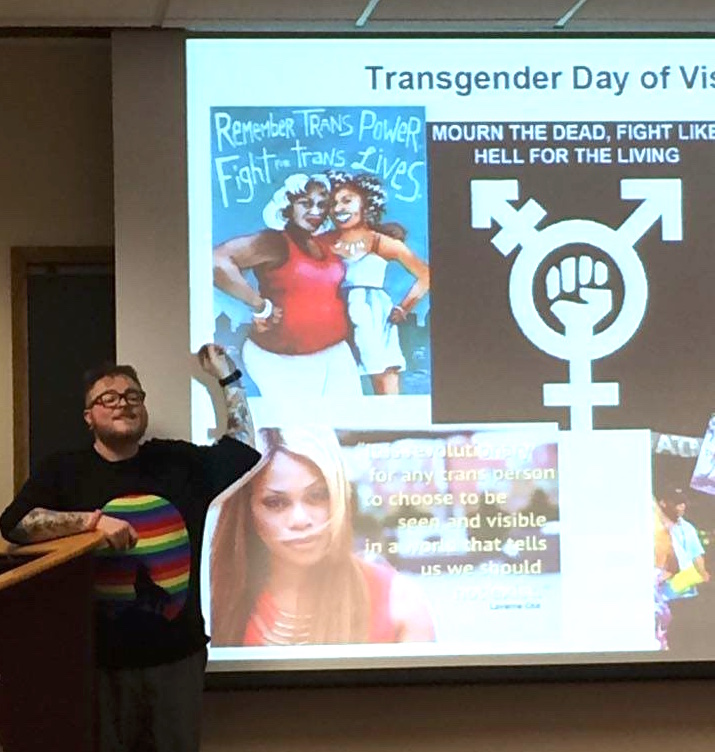

Even though he’s part of the transgender community, Stone has a deeper view of the experience of being trans than many other people do. He teaches in the Gender and Women’s Studies department at Western Michigan University and is working on his Ph.D. in sociology. For his dissertation, he’s been interviewing transgender people in Michigan about their experiences with discrimination and microaggressions.

Although it’s still early in the research process, one thing Stone says has struck him is the resiliency of the transgender people he has interviewed.

Although it’s still early in the research process, one thing Stone says has struck him is the resiliency of the transgender people he has interviewed.

“I’m talking to people about experiences with discrimination and microaggressions — subtle types of messages like ‘You’re unworthy’ or ‘We don’t respect you,’” he says. “A lot of times that’s unintentional, but it puts a lot of pressure on trans people.”

He says the emotional toll microaggressions take on transgender people has come up repeatedly in his research.

Trans people have to think about how they’ll respond to someone who may not even realize what they said was offensive, so it puts trans people in this very confusing place. But every person I’ve talked to has said, ‘I’m going to live my life for me and be free and be the person I want to be.’

Especially when I talk to trans people of color, people living in places where it’s more dangerous to be an out trans person, it says a lot about the ability of oppressed people to thrive — to really do more than survive, but to thrive.

Stone is open about the fact that he experiences anxiety and depression, even though he lives in an affirming community and has the unwavering support of his partner of nearly 11 years, Lisa, who has stayed at his side throughout his transition.

“If everyone had a partner like mine, there would be no more war in the world,” Stone says. “I feel incredibly, ridiculously lucky to have her in my life.”

He is also thankful for his friends and allies in Kalamazoo. In a few weeks, he’ll be teaching a class about so-called “bathroom bills” — which includes two now introduced in the Michigan Legislature — and “the debate over whether trans people are people with rights,” as Stone puts it.

It’s exhausting. There are people in Kalamazoo who have offered to talk to my class about these issues if I don’t feel like I can. Knowing there are others who can help with that if I’m not in the emotional place where I can be as effective as I want to be is a huge relief. If allies want to help, picking up that burden for someone is an example of how to be a great ally. I’m so grateful to have such amazing friends and allies.

In the end, Stone still doesn’t care about labels, but he has made his peace with them.

“The longer I’ve been on hormones and my outer physical appearance matches what society expects, the more free I feel I can be in the way I express myself,” he says. “But the label is not the most important thing. I’m just me.”

Read all the stories in this series HERE.

[Photos courtesy of Codie Stone, shown at top on Halloween with Butler.]