“That wouldn’t have been true, but I would have said it anyway.”

Donald Trump’s greatest asset is our good intentions.

It may be his only asset that he hasn’t mortgaged. Who knows? We haven’t seen his tax returns.

The latest example of Trump benefiting from the media’s fixation on the wrong hand in the sleight of hand trick is the debate about whether journalists should report that Trump is lying is even when he offers obvious untruths.

The worry? “[I]f you start ascribing a moral intent, as it were, to someone by saying that they’ve lied, I think you run the risk that you look like you are, like you’re not being objective,” explains Wall Street Journal editor in chief Gerard Baker.

Greg Sargent makes the case that Trump’s lies are “something new” that the press must confront aggressively:

If we don’t call that “lying,” or if we don’t squarely and prominently label these claims as “false,” don’t we risk enabling Trump’s apparent efforts to obliterate the possibility of agreement on shared reality? We’re already seeing a preview of how this will work in practice when Trump is president. On multiple occasions, Trump has dubiously claimed credit for jobs he has supposedly “saved,” and the headlines have tended to reflect his claims without also informing readers that those claims are unverified or open to doubt. People don’t always take the time to learn the details. Even when they do, if news orgs don’t take a clear stand on what is true and what isn’t, confusion can often follow.

The example Greg relies upon to reveal Trump’s logic is the “birther” campaign which “Trump himself originally conceived of … as a means of entree into the political consciousness of GOP primary voters.”

Here’s an even more specific example.

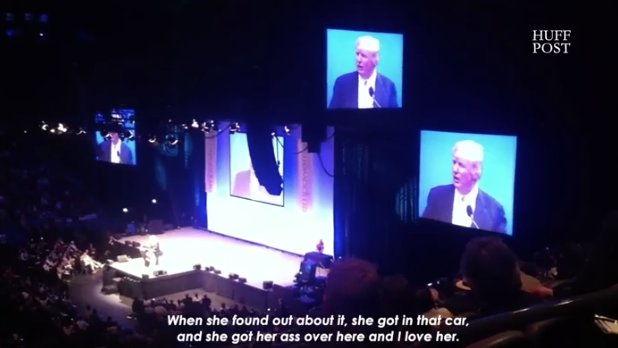

You may remember a video the Huffington Post highlighted as “Video Shows Donald Trump Sexually Humiliating Woman Before Large Audience.” Probably not.

It was merely a drop in the bucket of a series of reports of Trump’s expertise at being a sexual predator that followed the tape where he seemed to casually admit to serial assault and adultery. But there was an extremely telling moment in that video where Trump explained how his rhetoric works as he explains how he planned to get back at a Miss Universe winner who he’d been told didn’t want to introduce him:

“I was actually going to get up and tell you that Jennifer is a beautiful girl on the outside, but she’s not very bright,” he says, as the crowd laughs. “That wouldn’t have been true, but I would have said it anyway.”

There are other moments where Trump reveals that he’s lying about things he once inveighed about as if civilization depended on them — like locking up Hillary Clinton or “draining the swamp.”

Dilbert creator Scott Adams — who has won the right to be noted as the foremost interpreter of Trump’s tactics — wants us to understand that what Trump does to screw with our mind is intentional.

And Sean Spicer — Trump’s appointed White House Press Secretary — made a point of telling David Axelrod during a recent episode of CNN’s The Axe Files that Trump is a “very strategic thinker” who sets goals and works backwards to accomplish them. So we have to assume if he’s repeating false things he’s doing so “strategically,” which is the definition of a lie.

Frankly, as Newt Gingrich might say, it shows more respect to the next president if we give him the respect to assume that he’s lying and not just embarrassingly uninformed. (And the least we can do is offer Trump at least as much respect as he offered President Obama.)

The greatest trick the devil ever pulled was convincing the world he didn’t exist. And Trump’s greatest trick is convincing some of us that we live in a world we know doesn’t exist. It’s our job to at least point out that he’s doing this.