The following essay was written by my good friend Eli Savit. Eli is an attorney and an adjunct professor at the University of Michigan Law School. His areas of expertise include appellate and Supreme Court litigation; civil rights, education law, environmental law, and public-interest litigation. He writes regularly about legal issues on the Take Care Blog and elsewhere. Follow him on Twitter at @EliNSavit.

(On a personal note, Eli is an attorney who has, in large part, restored my faith in the profession.)

Enjoy (and please share widely.)

Late Friday afternoon — in typical news-dump fashion — Michigan Attorney General Bill Schuette issued a formal opinion which stated that Michigan’s Elliott-Larsen Civil Rights Act does not prohibit discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation or gender identity. Schuette’s opinion was in many ways predictable. The Attorney General, who infamously spent millions of taxpayer dollars fighting marriage equality all the way to the United States Supreme Court, has rarely missed an opportunity to stand against LGBTQ equality. His decision to insert his office into this issue was as unsurprising as it was disappointing.

Late Friday afternoon — in typical news-dump fashion — Michigan Attorney General Bill Schuette issued a formal opinion which stated that Michigan’s Elliott-Larsen Civil Rights Act does not prohibit discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation or gender identity. Schuette’s opinion was in many ways predictable. The Attorney General, who infamously spent millions of taxpayer dollars fighting marriage equality all the way to the United States Supreme Court, has rarely missed an opportunity to stand against LGBTQ equality. His decision to insert his office into this issue was as unsurprising as it was disappointing.

But it’s important to clarify a crucial point about Schuette’s latest anti-LGBTQ salvo. The opinion issued Friday has no force of law. It does not — and it cannot — change the legal landscape related to Michigan’s civil rights law. Powerful though his office may be, the Attorney General is not a judge. He has no authority to definitively interpret Michigan laws.

Here’s the background: In May, Michigan’s Civil Rights Commission ruled that Elliott-Larsen’s existing prohibition on discrimination “because of sex” prohibits discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity. The Commission was expressly empowered to make that ruling. In Michigan — as in the federal system — agencies are responsible for interpreting the laws they’re charged with enforcing. And the Commission is the agency charged with enforcing Elliott-Larsen.

The Commission’s ruling, moreover, was supported both by the law and by common sense. That’s because it’s impossible to discriminate on the basis of sexual orientation or gender identity without discriminating on the basis of sex. A gay man who is fired from his job on the basis of sexual orientation — i.e., because he is attracted to men — would not have been fired from his job if he were a woman attracted to men. Similarly, a transgender woman who is denied service at a restaurant on the basis of gender identity would not have been denied service if she were assigned the sex “female” at birth. Discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity, in short, is discrimination “because of sex.” Multiple federal courts agree. The federal Civil Rights Act contains identical language prohibiting discrimination “because of sex.” And over the past several years, a torrent of federal decisions have held that language prohibits discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity.

The Commission was thus squarely within its legal authority to issue its interpretive ruling. Not only was the Commission empowered to interpret the law, its decision was reasonable, well-justified, and consistent with the decisions of multiple jurists.

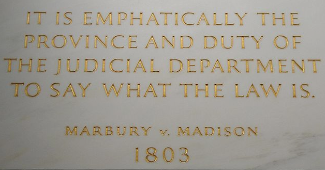

That doesn’t mean that the Commission has the last word. It is a foundational principle of American law that courts have the final authority to interpret the law. And the Elliott-Larsen Civil Rights Act provides a simple route through which the Commission’s interpretation of the law can be reviewed by a court. If an agency gets its interpretation of the law wrong, in other words, courts can and will correct it.

That doesn’t mean that the Commission has the last word. It is a foundational principle of American law that courts have the final authority to interpret the law. And the Elliott-Larsen Civil Rights Act provides a simple route through which the Commission’s interpretation of the law can be reviewed by a court. If an agency gets its interpretation of the law wrong, in other words, courts can and will correct it.

The key point, though, is that the judiciary is the only branch of government that has the authority to review the Commission’s interpretation of the law. The Michigan Supreme Court has made absolutely clear that an agency’s interpretation of the law will be followed “unless and until the statute is otherwise authoritatively interpreted by the courts.” There is no process by which the Attorney General can review and override an agency’s interpretation.

All of that makes Schuette’s “formal opinion” legally befuddling. As the state’s top law-enforcement official, Schuette must be aware of the foundational legal principle that only courts can override agency interpretations of the law. He must be aware of the Michigan Supreme Court’s holding that “an opinion of the Attorney General … does not compel agreement by a government agency.” And he must further be aware of recent Supreme Court decisions waving aside any suggestion that the attorney general can bind a state agency.

Nevertheless, Schuette issued an “opinion” which called the Commission’s interpretation of the law “invalid.” But that opinion cannot actually invalidate the Commission’s interpretation. Nor can the Attorney General force the Commission to comply with his own preferred interpretation of the law. The Attorney General is not a judge, and his opinions are not judicial decisions. At bottom, Schuette’s “formal opinion” is entitled to only slightly more legal consideration than a Tweet or a Facebook post.

All of this is important — and not just because of the crucial need to afford LGBTQ Michiganders the same civil rights as all of us enjoy. We have a constitutional system in this country in which the judiciary is empowered make definitive interpretations about the law. The Attorney General can’t just seize judicial power for himself. If he could, it would upset our careful system of checks and balances.

So, take Bill Schuette’s “opinion” for what it is. It’s a politician’s political essay, which seeks to (once again) beat up LGBTQ Michiganders to curry favor with his far-right base. But it cannot, and it should not, be read to override the Commission’s interpretation of the law. If it were, it would inflict great harm — not just to LGBTQ Michiganders, but to our system of constitutional governance as a whole.