The Thomas B. Fordham Institute is a conservative think tank focused on education policy issues. One of their frequent contributors is a person named Dale Chu. Full disclosure: I do not know Mr. Chu, we’ve never met, and I’ve only glanced at his blog posts in the past. I do know that I’ve never run across any of his scholarly policy work in my readings, or seen him speak at any major educational conferences I’ve attended over the years–but could chalk that up to our running in different academic circles. And I’m sure he’s never heard of me, either.

Now that we have that out of the way, I was simply flummoxed after reading his latest effort for the Fordham folks, “The million-dollar question: What will it take to improve education in America?” I’ve got to hand it to Mr. Chu: he’s got that academic title generation thing down, colon and all. And as someone who spends an inordinate amount of time thinking about how to improve education in America, he had me at the title–I was hooked.

So in I dove, only to find an embarrassingly flimsy Top 10 mist of Mr. Chu’s “ideas” to improve our schools. Coming “from someone who spends his waking hours ruminating on the subject,” as Mr. Chu describes himself, I was hoping to see a thoughtful, well-reasoned list of topics that are currently impacting America’s public schools–the schools that 90% of our kids attend. Things like school funding, teacher pay, teacher evaluation systems, standardized testing, and a whole raft of other pressing problems.

Instead, what I found was a flimsy set of ideas based on a breathtakingly uninformed premise:

“What’s the goal of our education system?” The idea of “improving” anything suggests measurement, and it’s easier to assess progress when there’s a clear end in mind. These days, a popular goal for our schools is workforce preparation, which has been in large part driven by business-led reform coalitions.

At the risk of being rude, no and no.

It’s not a “popular goal” of education to produce a workforce–that’s a by-product of schooling, not a goal. Reasonable persons can disagree on the “purpose(s) of education”, but it’s really not something so narrow and restrictive as “workforce preparation”–unless you own a widget factory, and would like the public schools to offer more “widget making” classes, so you don’t need to provide any workplace training on widget making, thus saving your business millions in additional employees to develop and teach these classes, and resulting in an abundance of “trained” widget makers, so you can further reduce the starting wages of your annual crop of novice widget makers. But I digress…

Perhaps even more disturbing, however, was Mr. Chu’s assertion that “the idea of ‘improving’ anything suggests measurement”, a statement that reveals an exceedingly regressive and atomistic view of how human beings operate in the world–and especially in schools. Contrary to Mr. Chu’s apparent belief that we “measure what we treasure”, I’d suggest that exactly the opposite is actually true–that the things we love best, and value the most, are precisely those things that are the most resistant to being measured. And if you doubt this to be true, I invite you to try a little experiment tonight: When you get home from work, or school, or whatever you spent your day doing, walk into your house or apartment or dorm, and tell your friend, partner, roommate, or spouse how they did today in meeting your needs, expressed on an “A to F” grade scale. And if you happen to be a parent, assign grades to your children based on how much you love them. And then please let me know how that works out for you. But I digress, yet again…

After the shock of this garbled premise wore off, I plunged into Dale’s list of ideas, and here are a few of my thoughts–which are exactly as random as his list:

- Chu: Ten years ago, the prevailing wisdom among policy architects was to bet on higher standards, assessment, and accountability. The luster on these have since worn off…

It’s been fascinating to see so many among the “ed reform crowd” start backpedaling from their previously unquestioned belief in the sanctity of higher standards and the holy grail of accountability. Stalwarts in the movement like Peter Cunningham couldn’t type out a complete sentence for years without using the “A” word multiple times. But now, the acolytes in the Church of Reform seem to have finally heard what teachers have been screaming at them for years: education is already the most highly-scrutinized and accountable sector of the nation’s economy, and teachers are doing heroic work under absolutely wretched conditions. So enough with the constant harping on “more accountability” and “higher standards”, and let’s start hearing more from policy wonks and our elected leaders about “more resources for schools and students” and “higher teacher salaries” for a change. Because every time I hear one of the reformers or politicians mumble something about how “throwing money at the schools won’t improve anything,” a little voice inside my head says, “Maybe so…but it’s about the only thing we haven’t done yet…so let’s give it a try!” - Chu: Any effort to improve schools won’t have the desired effect if those charged with implementation don’t find the effort to be credible. As I type this I’m sitting at my desk just shaking my head. Virtually none of the contributors to the Fordham Institute’s blog roster are, or ever were, teachers. And here’s Mr. Chu opining that the policy ideas he’s dreamed up over the years just won’t work unless the folks charged with implementing those ideas (i.e., teachers) are on board. In the collective voice of America’s professional educators, Dale…”duh.” (And for the record, I understand that Mr. Chu began his “career” in education through a stint with Teach for America, the ed policy training organization disguised as an alternative route to teaching certification program…and no, I do not consider TfA recruits to be “teachers”.)

- Chu: There’s a lot of room for improvement when it comes to rethinking how teachers enter the profession. From recruitment and barriers to entry (e.g., testing and fees) to diversity and licensure, preparation is a lever that policymakers will continue to pull. Last year, I moderated a panel discussion that asked whether the teaching profession should be more like medicine (difficult to enter, years of training, high prestige) or journalism (no formal training required and opportunities for quick advancement and exit). Participants overwhelmingly voted for the latter, but the question is far from settled.

I’ve been a teacher since 1980, and have literally never heard a real, live teacher suggest how great it would be if there was no formal training required to enter the profession, and it was even easier to turn teaching into an entry-level gig to be used for a year or 2 as a stepping stone to bigger and better things. I have heard lots of teachers and teacher educators talk about new models of teacher preparation based on the medical school model of internships and paid residencies, with plenty of professional development and guided supervision and mentoring…but have never heard of a policy wonk or politician suggesting where we’d find the dollars to create such a model. So while I’m not doubting that Mr. Chu’s panelists voted for the “journalism model” (quick side note: my journalist friends don’t think this “model” works all that well in their line of work, either), I am doubting that this panel was devoted to thoughtful considerations of improving education. (Spoiler alert: The panel was organized by TeachPlus, a Gates Foundation-funded astro-turf organization dedicated to destabilizing teacher professionalism. Their big policy “wins” lately have been bills designed to terminate large numbers of experienced teachers in states like Indiana and Florida. Kind of an odd thing for “experienced teacher leaders” to get behind, eh?)

Now, are there things to be improved in teacher preparation? Absolutely. Perhaps the biggest would be to remove the obstacles being thrown at our programs from policy groups like TeachPlus and the Fordham Institute that have nothing to do with “improvement,” and everything to do with destroying public education, and colleges and schools of education as center of educational policy deliberation. The truth is that today’s teachers are the best they’ve ever been; more broadly prepared, with richer pedagogical strategies, and a more diverse array of skills and knowledge than ever before. It’s a shame the ed reformers don’t get out of their way and let them teach. Because they are spectacular. - Chu: Whether you call it school choice or parental choice—and some argue there’s a subtle yet important difference between the two—it’s an option that is still largely limited to those with means. Universal educational choice could help to level the playing field and strike a powerful blow for social justice. With the bewildering array of decisions that go into creating and sustaining a great school, there’s something to be said about letting schools figure out all of this stuff on their own, and letting parents choose the school that matches their values.

It took until #8 on his list, but we finally get to crown jewel of the reform agenda: school choice. But I’ve got to give Dale some credit here for creative thinking, because he’s attached his rationale for choice (letting parents choose the school that matches their values) to the thing about choice schools that makes it impossible for his rationale to be true (the lack of local control over school governance in charter and private voucher schools.) It’s either a blind spot in Mr. Chu’s understanding of the educational landscape, or a pretty cynical “take” on the ignorance of the American public when it comes to education–or both, probably.

The truth is that school choice is a false choice, and the problems created by competition and choice will not be solved by competition and choice. Mr. Chu either doesn’t know this, or doesn’t care, and neither one is a good look. - Chu: Finally, there are those who argue that the system as it currently exists works perfectly fine for the era it was designed for (think the G.I. Bill and universal high school). In this view, education is wrongly perceived as broken. Moreover, the thinking goes, we won’t make any headway unless we solve larger societal issues like poverty or institutional racism—though for better or for worse, reformers tend to part ways when it comes to race.

More truth: Education is not “broken, doesn’t need to be “fixed,” and is not “failing.” We have failed our schools…and our children.” Mr. Chu is pushing the hackneyed myth, taken up most recently by another well-known edutourist, US Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos, that schools have not changed since the Industrial Age, and are nothing more than stodgy relics of a bygone era.

The only persons who could say such a thing are persons like Mrs. DeVos, who never attended a public school, never studied education, and never spent a day in a public school teaching anything to anyone. A teacher from the 1940s wouldn’t recognize a school today, with the explosion of technology (both good and bad), media, and curricular change. My last year of public school teaching was 1993, and I often feel like a visitor from the past when I spend a day in a public school. Things have changed. Teachers have changed. Kids have changed. And learning has changed.

To be sure, more change still needs to happen. Over 80% of the nation’s teachers are white, and there’s an urgent need for more teachers of color, more women in science and math, and more men in elementary schools. We also need more teachers who are bilingual, and more teachers who are prepared to work with children with special learning needs. Also, we simply need more teachers–the constant attacks on teaching as a profession, under the guise of “More Accountability!,” have taken a toll, and the teaching shortage grows more acute by the day–especially in our urban and rural communities.

We also need to expand and enhance what we are teaching so that it’s more relevant and meaningful to an increasingly diverse audience of learners in our schools. We need to teach and celebrate more kinds of music, art, and new approaches to teaching history and social studies, always taking care to tell the stories of all of our learners–not just the ones whose stories have been privileged over the years.

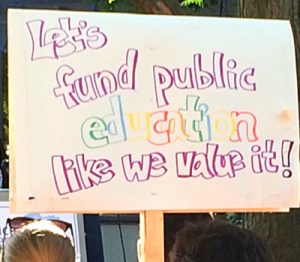

And we need to put our money where our mouths are, devoting the resources to the things we say that we value–our children and their education–by fully funding our schools, maintaining and rehabilitating our school facilities, paying our teachers respectable salaries (so they don’t need to work 2 and 3 jobs to make ends meet), and improving teachers’ working conditions (which equal students’ learning conditions.)

Interestingly, none of the things I’ve just mentioned managed to even crack Mr. Chu’s Top 10 list, suggesting that his “million dollar question” wasn’t really a very serious question at all. Which he would have known if he’d simply asked a teacher.