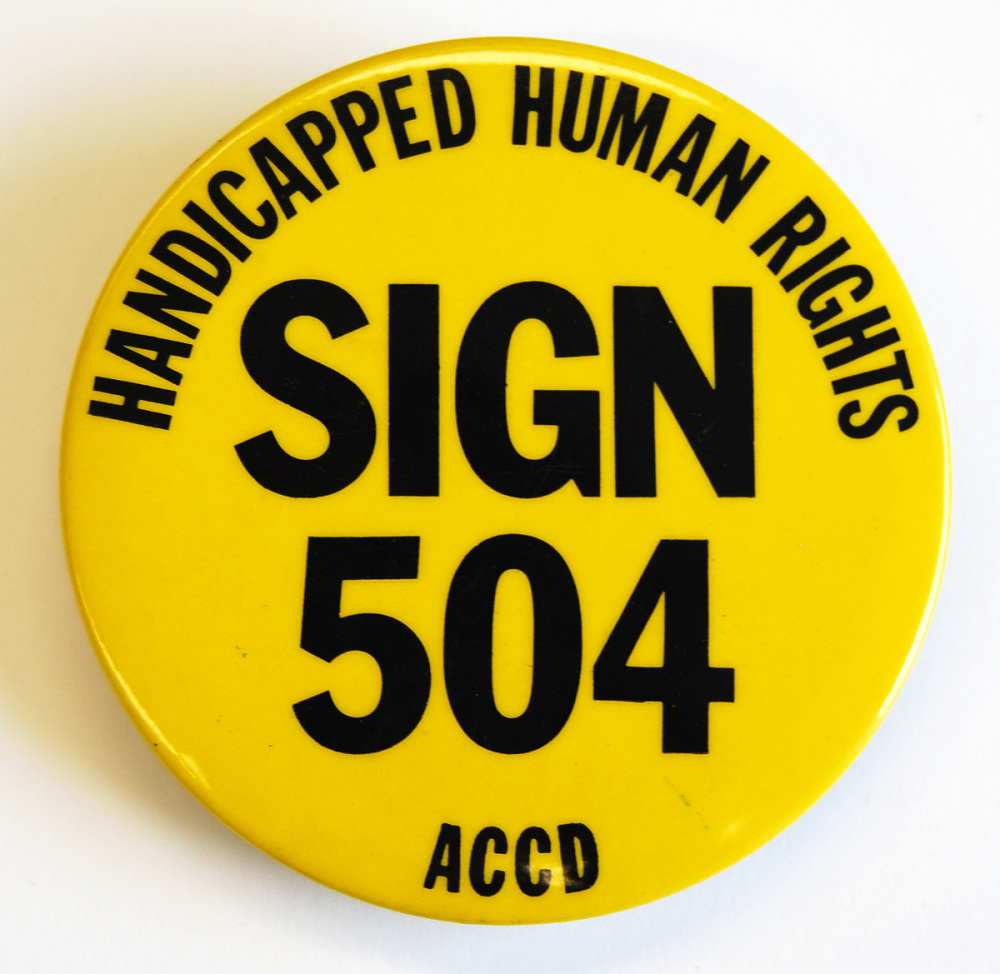

In 1977, the longest occupation of a federal building in the history of the United States of America took place and, when it ended, the protesters had achieved what nobody thought possible: regulations covering the enforcement of a four-year old law — Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973. The protest is now called “The 504 Sit-In” and for over three weeks, members of the disability community occupied the Federal Building at 50 United Nations Plaza in San Francisco, which housed the regional office of the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare (HEW), the federal agency tasked with creating the regulations required by Rehabilitation Act.

Section 504 states, in part:

No otherwise qualified individual with a disability in the United States, as defined in section 705(20) of this title, shall, solely by reason of her or his disability, be excluded from the participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any program or activity receiving federal financial assistance or under any program or activity conducted by any Executive agency or by the United States Postal Service.

The original protest rally at the HEW office in San Francisco was part of nationwide day of protests which began on 44 years ago today on April 5th. Unlike the protests in other cities, the organizers of the San Francisco rally had been quietly planning an occupation of the office there. Occupiers came to the rally with backpacks filled with some essentials and, when the rally concluded, the entered the building and refused to leave until HEW Secretary Joseph Califano signed the Section 504 regulations which gave guidance on how the law would be enforced.

The original protest rally at the HEW office in San Francisco was part of nationwide day of protests which began on 44 years ago today on April 5th. Unlike the protests in other cities, the organizers of the San Francisco rally had been quietly planning an occupation of the office there. Occupiers came to the rally with backpacks filled with some essentials and, when the rally concluded, the entered the building and refused to leave until HEW Secretary Joseph Califano signed the Section 504 regulations which gave guidance on how the law would be enforced.

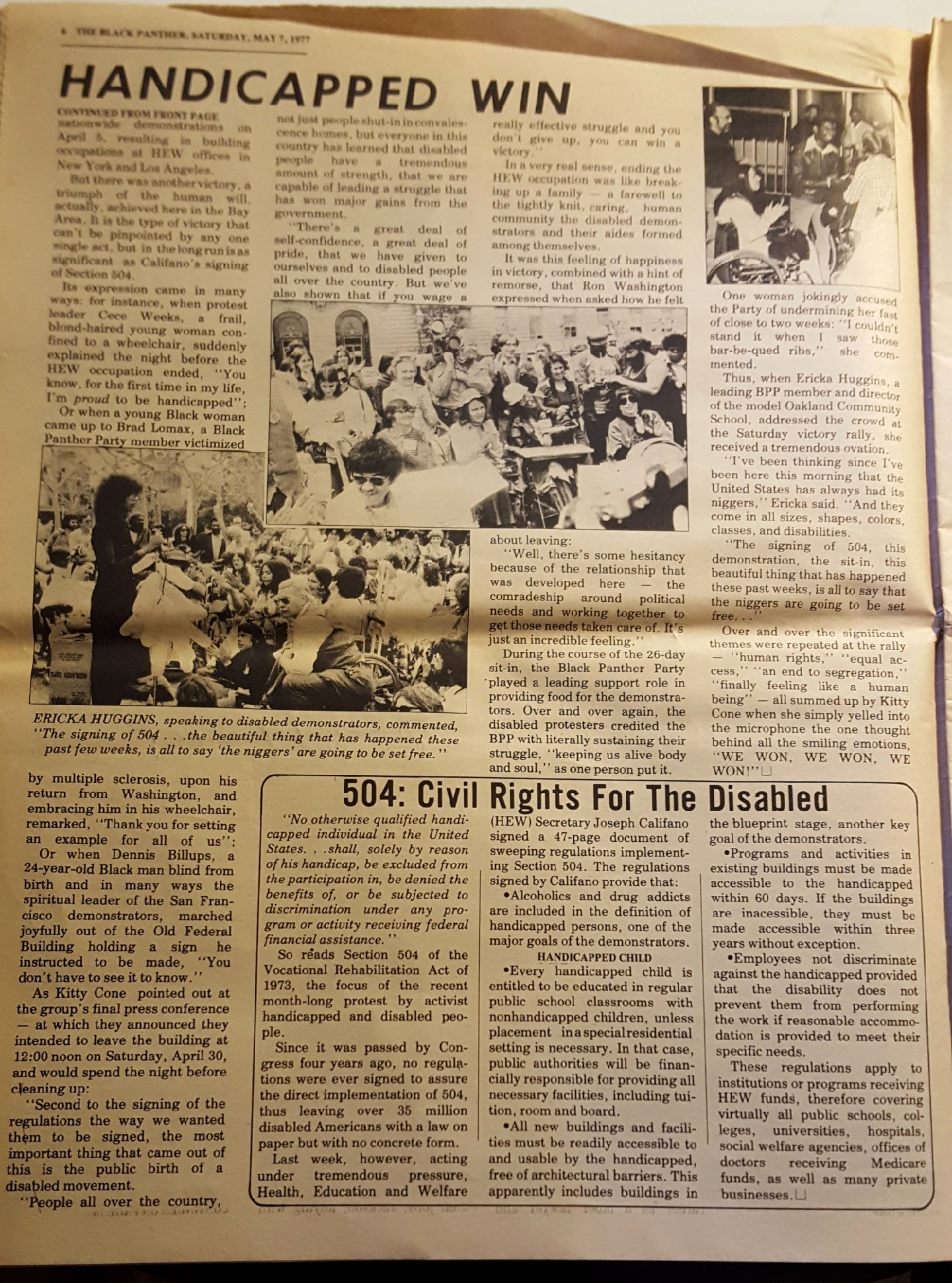

Stories from the nearly month-long occupation are riveting and dramatic. Over 100 people with disabilities of all kinds participated. People with deafness. People with blindness. People living with paraplegia, even quadraplegia. People with mental disabilities. People using wheel chairs. Men, women, straight, and queer. This committed group formed a community where everyone played a role and where everyone helped each other. They bathed in sinks. They created a makeshift refrigerator for storing medicines by encasing an air conditioner in tarps. Those with blindness attended to people with mobility issues who reciprocated by reading written materials to them.

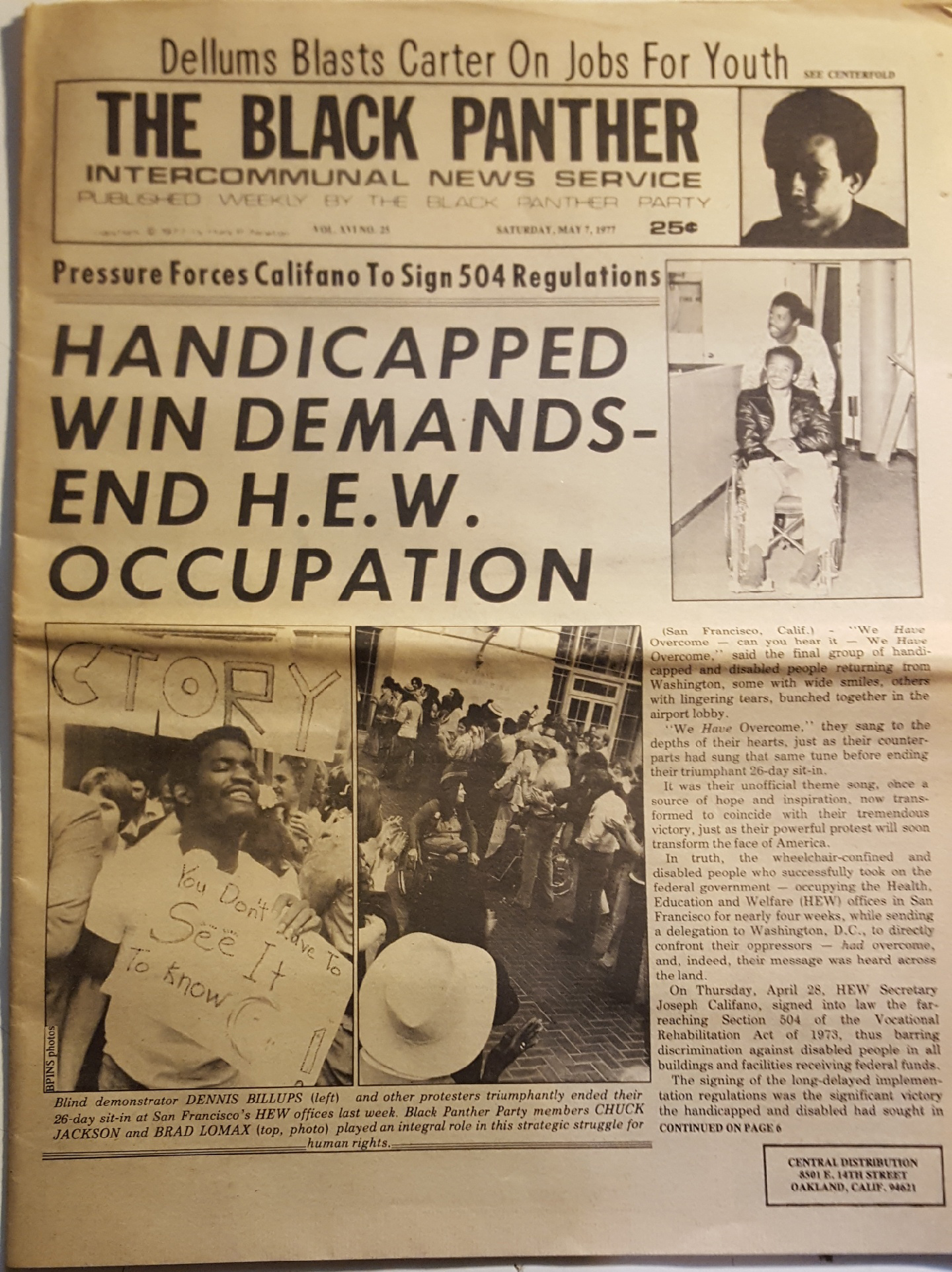

After a time, telephone service was cut off to the building in an attempt to prevent them from communicating with outside allies and the media. Deaf individuals took over, communicating using American Sign Language with those outside the building through windows to get their messages out. Allies from all quarters joined in the effort, bringing supplies, mattresses, portable showers, and other items. The Black Panthers, who had members Brad Lomax and Chuck Jackson inside the building, began to supply daily nourishing meals. One of the true hallmarks of this successful action was the cross-demographic solidarity forged in advance and during the occupation by the organizers.

After a bit over a week, the protesters worked with representatives Philip Burton and George Miller to host a day-long hearing inside the building to educate the nation about their fight:

The sympathetic politicians declared the 4th floor of 50 UN Plaza “a satellite office of Congress,” which brought television and newspaper reporters. As cameras rolled, dozens of protesters testified on one of several panels related to specific disabling conditions: blindness, deafness, addiction, and others. In a highly public way, people with disabilities were educating Americans about low employment rates, housing discrimination, lack of educational opportunities.

Before the sit-in concluded, a contingent of protesters representing people with nearly all types of disabilities loaded into the back of a moving van equipped with a cargo lift that had been rented by the International Association of Machinists labor union and made an arduous trip to Washington, D.C. Once in DC, they held protests, met with lawmakers, and held vigils. Given the difficulties of getting around in the days before the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), the trip in the back of the dark van along with the subsequent actions took enormous fortitude, stamina, and determination.

More details about this incredible action can be found HERE, HERE, HERE, and HERE, as well as in the documentary Crip Camp – A Disability Revolution, available on Netflix.

Califano signed the regulations on April 28, 1977 and America was transformed. For the first time, access to the society was opened a bit wider for people with disabilities. Years later, when the ADA was passed, this access was expanded further.

Click images for larger versions

In commemoration of the 504 Sit In, the amazing disability advocacy group, Detroit Disability Power, is conducting a member recruitment drive. They hope to gain 100 new members by the end of April. Here’s the message from my friend, the incredible activist Dessa Cosma, Executive Director of Detroit Disability Power:

In commemoration of the 504 Sit In, the amazing disability advocacy group, Detroit Disability Power, is conducting a member recruitment drive. They hope to gain 100 new members by the end of April. Here’s the message from my friend, the incredible activist Dessa Cosma, Executive Director of Detroit Disability Power:

We have the 504 Sit-In protest to thank for curb cuts, ASL interpreters, and so many other aspects of daily life that are essential for full participation of disabled people in American society.

Essential, but not sufficient. Today, in 2021, policies and systems that exclude people with disabilities still dominate our world in Detroit and Michigan. Detroit Disability Power mobilizes hundreds of people to demand better — and those demands are heard! Over the past two months, DDP has worked with other organizations to get Detroit, counties and the state of Michigan to prioritize disabled people for access to Covid-19 vaccines.

You may have been one of the hundreds who amplified the call for vaccine priority and helped win those victories. Now, we are asking you to become a member to show the power of our movement so we can all achieve even more.

In 1977, over 100 people put their bodies on the line to make a difference for disability rights. Today, you can make a difference by joining your political voice with ours. The sign-up form asks you to pay dues at whatever level you can afford (can be as little as $5/year). As a member, you’ll be able to weigh in on DDP’s direction — and your impact on our region’s policy will be multiplied.

DDP’s efforts to build a humane and equitable society have the greatest impact when we speak as a large network of knowledgeable, passionate activists. By joining as an official member, you will build power for yourself and others seeking justice in Detroit and beyond. Check out our Member Manual for details on membership.

I look forward to sharing more of the story of the 504 sit-in with you, and I look forward to announcing DDP’s next milestone of 100 members. Please act today to become one of our first 100. Without you, we’re less. With you, we can go further toward justice now.

You can listen to our interview last year with Dessa Cosma on The GOTMFV Show podcast HERE.

The 504 Sit-In showed the power of cross-demographic solidarity in creating significant change. Today Detroit Disability Power is forging a civil rights coalition for the 21st Century, one where we all build power and access for ourselves and others, collectively, passionately, and with love and compassion for everyone.

Please join me by becoming a member today.

[Button image via the National Museum of American History. Newspaper images credit: Billy X Jennings | Black Panther Party Archives. Detroit Disability Power image credit: Shin-Yi Wang | Detroit Disability Power]