As America emerges from the Dark Year of the COVID-19 pandemic, one thing is crystal clear: we have a childcare crisis in this country. While jobs are opening up nearly everywhere, employers struggle to find employees to fill their vacant positions. One reason is that the jobs people are being offered pay less than the ones they left due to the pandemic.

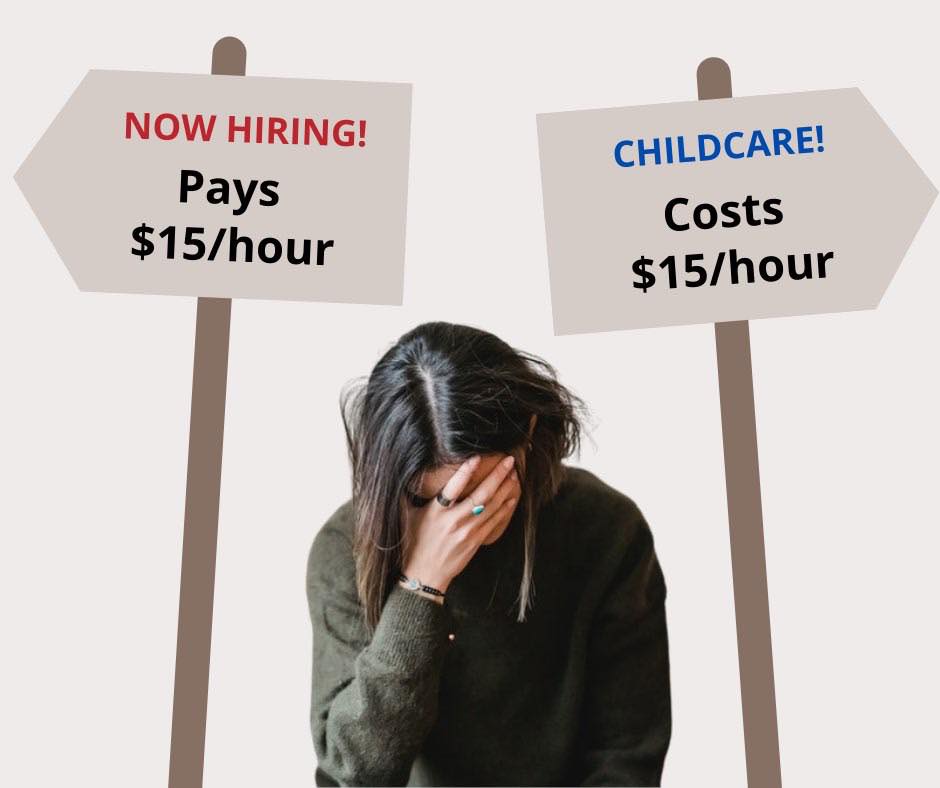

However, a bigger issue is that childcare has become unaffordable for most families; now more than ever. A significant portion of the potential workforce are having to chose between staying home with their kids or taking a job that barely covers their childcare costs.

However, a bigger issue is that childcare has become unaffordable for most families; now more than ever. A significant portion of the potential workforce are having to chose between staying home with their kids or taking a job that barely covers their childcare costs.

On top of that, despite the high costs of childcare, childcare providers aren’t being paid wages commensurate with their service to society. As one person put it to me recently, childcare isn’t too expensive, it’s unaffordable, and childcare workers deserve every single cent they earn and then some.

This result of this will be an ever-widening gulf between wealthy families and those of more modest means. It also means more children in poverty with worse developmental opportunities. It is a real problem that will require a federal response if the U.S. economy is ever going to return to its pre-pandemic robustness.

The answer: Universal childcare.

You might think that universal childcare is a pipe dream that could never happen in America. But, the truth is, we have done this before.

You might think that universal childcare is a pipe dream that could never happen in America. But, the truth is, we have done this before.

On June 29, 1943, the U.S. Senate passed legislation that created the first and, so far, ONLY national childcare program in American history. It was part of a larger program passed earlier known as the Lanham Act which funded infrastructure around the country to support the wartime effort. Two newly created agencies, War Public Works (WPW) and War Public Services (WPS), were responsible for executing the provisions of the Lanham Act and WPS focused almost exclusively on childcare.

There was an incredible need for this program because women, who had been a tiny proportion of the workforce prior the start of World War II in 1939, were making up an increasing share. At the height of the war, in fact, nearly a quarter of all married women were working outside the home and 36% of all women of working age were in the workforce. They worked in a number of industries making things like munitions and, like the famous Rosie the Riveter, building aircraft. These women were desperate for reliable childcare and so were the companies they worked for who were struggling with absenteeism in women who had limited or no access to care for their children.

There was an incredible need for this program because women, who had been a tiny proportion of the workforce prior the start of World War II in 1939, were making up an increasing share. At the height of the war, in fact, nearly a quarter of all married women were working outside the home and 36% of all women of working age were in the workforce. They worked in a number of industries making things like munitions and, like the famous Rosie the Riveter, building aircraft. These women were desperate for reliable childcare and so were the companies they worked for who were struggling with absenteeism in women who had limited or no access to care for their children.

Congress dedicated $52 million for this effort, an amount equivalent to over $800 million in 2021 dollars. With contributions from state and local governments, a total of $78 million (over $1.2 billion today) was dedicated to making universal childcare a reality in America.

Communities, mostly through user fees, contributed an additional $26 million. At its July 1944 peak, 3,102 federally subsidized child care centers, with 130,000 children enrolled, were located in all but one state and in D.C. By the end of the war, between 550,000 and 600,000 children are estimated to have received some care from Lanham Act programs.

As the war began to turn in the direction of the Allies, the funding began to dry up. However, they added another $7 million (almost $108 million today) after Americans around the country aggressively lobbied Congress.

[A]fter the drop in war production needs following the spring 1945 Allied victory in Europe, the FWA granted fewer project approvals or renewals. In mid-August 1945, once victory in Japan was assured, the agency announced all Lanham Act funding of childcare centers would cease as soon as possible, but in no case later than the end of October 1945. Approximately 1 month after this announcement, the FWA reported it had received 1,155 letters, 318 wires, 794 postcards, and petitions signed by 3,647 individuals urging continuation of the program. Principle reasons given were the need of servicemen’s wives to continue employment until their husbands returned, the ongoing need of mothers who were the sole support of the children, and inadequacy of other forms of care in the community.

The success of the Lanham Act in answering the country’s need for widespread, affordable childcare is a vivid demonstration of what we can do collectively when we are in a moment of crisis. What drove the need in the early 1940s was the large proportion of women in the workplace. And, in 2021, that proportion is even higher than it was at the height of World War II. Today, nearly 60% of women work outside the home, over 1½ times the number during the war. But in 2021, families do not have access to the type of programs created by the Lanham Act.

If there was ever proof the childcare is infrastructure, the Lanham Act is it. We need a 21st Century Lanham Act for America to make sure our economy surges back and no family is left behind.

[WW II childcare center photos credit: Gordon Parks for the U.S. Farm Security Administration/Office of War Information via the U.S. Library of Congress. Childcare costs vs. wages image credit: Alex Zolkowski, used with permission.]