The following article was written by Collin McDonough (@acomplexcollin) and Nicholas Golina (@GolinaNick).

Collin is a recovering legislative staffer. He is a Policy Advisor at Data for Progress, a freelance data scientist, and is co-founder of Momentum Advocacy. He holds a Bachelor’s degree in Political Science from Michigan State University; has a certificate in Data Science from Johns Hopkins University; and is a JD/MA-Economics candidate and an MS-Applied Data Science candidate at Wayne State Law School and Syracuse University, respectively.

Nicholas is a freelance data scientist, co-founder of Momentum Advocacy and activist who does work for multiple campaigns and organizations including Ohio for Bernie, the NAACP, and WolfPAC Ohio. He is also a graduate student at Kent State University in Data Science with his Bachelor’s degree in Labor Economics from the University of Akron.

For more discussion about Modern Monetary Theory, see our podcast episode with Professor Stephanie Kelton, “Burn the Debt Clock!” HERE.

Enjoy.

Modern Monetary Theory: The Third Hand of Economics

Harry Truman is famous for requesting a one-armed economist. When he posed a question to economists, answers would all follow the same simple structure: “On the one hand, you’ll get this. But on the other hand…”

Broadly speaking, typical discussion of fiscal and monetary policy revolves around two separate trains of thought: On one hand, you have the Orthodox (neoclassical) approach and on the other hand, there are various versions of the Heterodox (Keynesian, Marxist, Post Keynesian, Institutionalist, Modern Monetary Theory) theories. The orthodox approach aims to study the allocation of scarce resources among unlimited wants (Mitchell, p. 5). Guided by Adam Smith’s “Invisible Hand” theory, this camp seeks to maximize pleasure through self-interest and markets unhampered by governmental interference. The Heterodox camp, on the other hand, defines economics as the study of social creation and distribution of society’s resources (Mitchell, p. 7). Under this theory, government activity impacts the markets to provide resources and stability for the people. In this article, we will explore a third, lesser-known Heterodox option: Modern Monetary Theory (MMT).

Overview of MMT

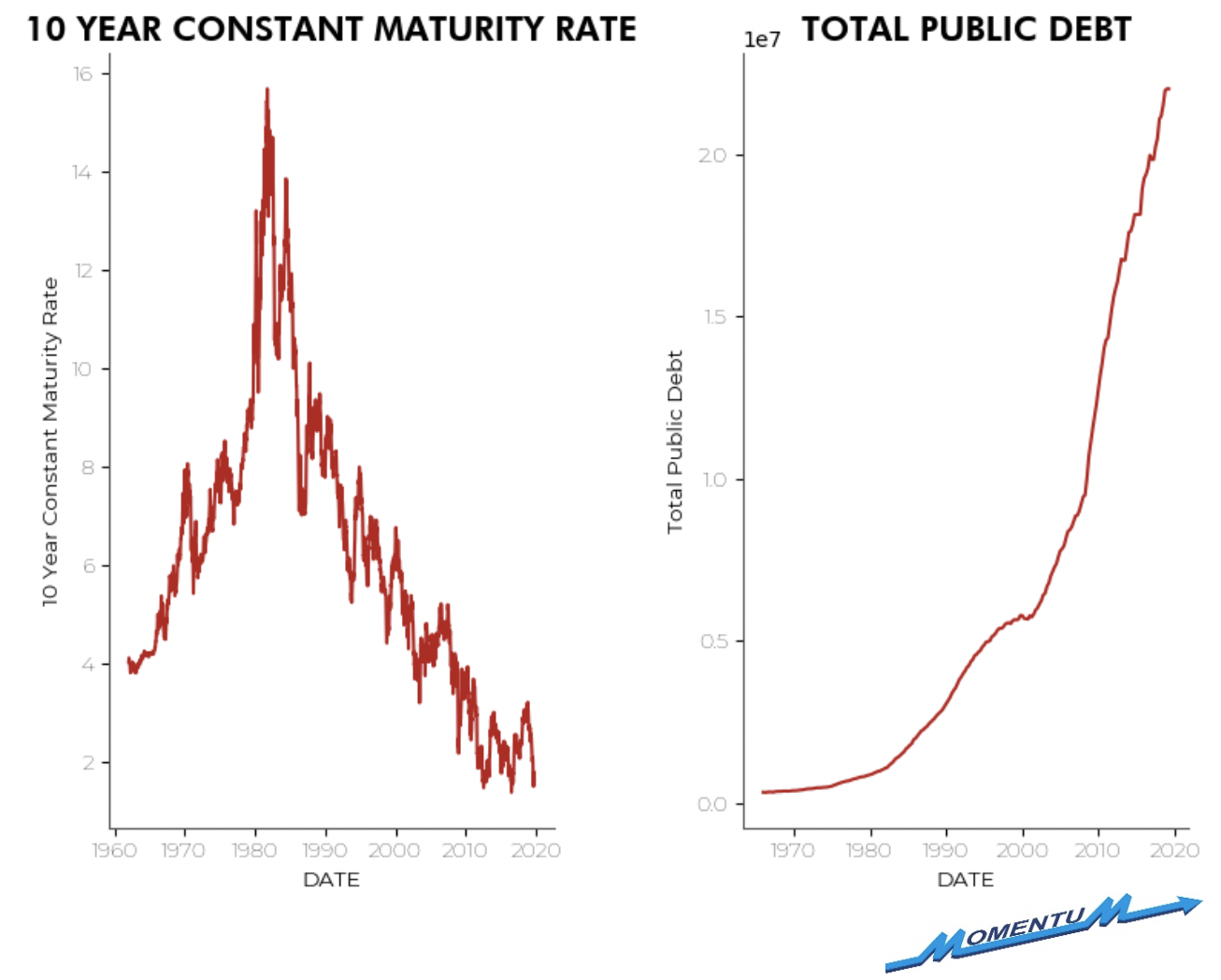

While a branch off the Heterodox theories, the basic tenet of MMT is that in a sovereign nation with a sovereign currency, the government can never run out of money or be forced to miss a payment on any payment denominated in its own unit of currency. As James Juniper describes it, “Full fiscal-monetary sovereignty exists when the consolidated government sector (Treasury and Central Bank) of a country issues a fiat, nonconvertible currency and operates with a flexible exchange rate” (Juniper, 284). For proof of this, you need to look no further than our history of Treasury bonds over the last half-century. According to data from the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis (FRED), the US 10-year constant maturity rate (an important measure of borrowing costs) are at their lowest levels since the 1960s even when the total public debt has been increasing over the decades.

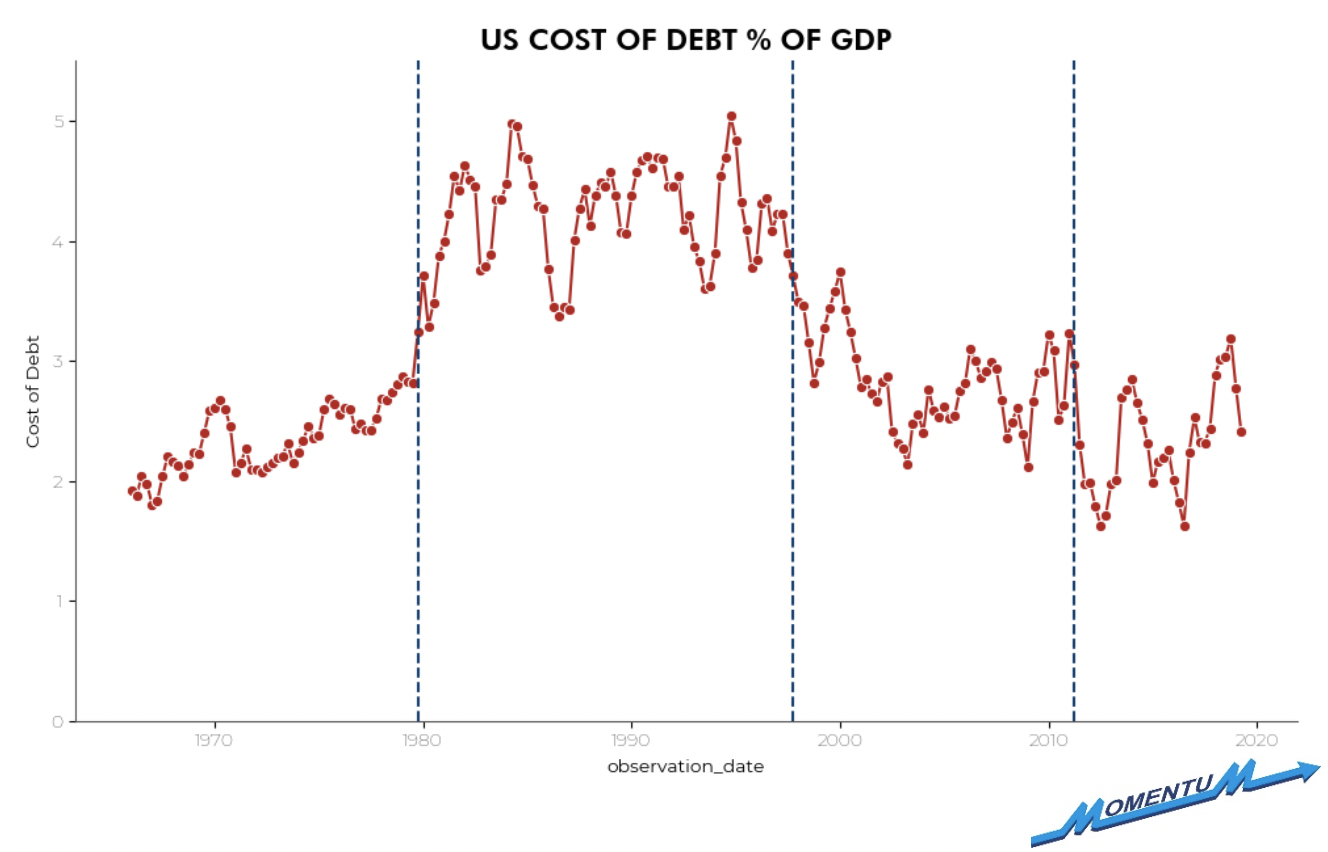

It is true that the debt-to-GDP ratio for the US is high based on data from the orthodox economist Carmen Reinhart. However, when taking into account the 10-year constant maturity rate, the actual cost of debt in the United States demonstrates nearly the same trends as the aforementioned FRED data. Additionally, the cost of debt in the US has never once reached above six percent of GDP, which indicates that borrowing costs have never been high at any point in modern US history. Finally, our structural break analysis indicated that the 4th quarter of 1997 was the point where the cost of debt started to see a statistically significant decline compared to the previous time frame. Consequently, borrowing costs have not reached above 3.5 percent.

Furthermore, data from Reinhart also documented that since its inception, the United States has never once had an external default on its debt. From this we can make one of the central observations of MMT: Since the US has a monopoly over the issuing of its own currency, it can therefore control its borrowing costs.

While not aligned with either political party—as both Democrats and Republicans frame the problem of budgets through the wrong mindset—MMT has been brought to new light after Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez said it should be “A larger part of the conversation.”

We’re currently stuck in a system dominated by austerity politics and economics. With deficit hawks on the Right and the current Democratic-controlled Congress enacting a policy of PAYGO (only enacting policies that will not add to the federal debt), we are limiting our ability to pursue ambitious policy changes—things like the Green New Deal, Medicare-for-All, and tuition-free college.

Simply put, MMT shows the way we think about budget constraints and deficits are wrong. Government deficits do have an impact on the economy—in the form of non-government surpluses. Using T-charts for double-sided accounting, we can look at it this way: aside from taxes, every dollar the government spends goes into the hands of the private-sector. Therefore, an inverse relationship exists between government deficits and private-sector surpluses; This is known as the sector financial balances equation (Private-sector Surplus = Government Deficit + Currency Account Surplus (or S-I = (G-T) + (X-M)). When the government spends on things like infrastructure, healthcare, education, or poverty-alleviating measures, the non-government sector benefits. The inverse is also true; When the government runs surpluses, the private-sector runs deficits. “This accounting reality [government deficits are the sole source of net financial assets for the non-government sector] means that if the non-government sector wants to net save in the currency of issue, then the government has to be in deficit.” (Mitchell, 125.)

There have been seven times throughout American history where the government has run a budget surplus. Within five years of each of these surpluses, the United States has faced either a recession or a depression. The private-sector cannot simply “keystroke” its way into more money; The government can.

Hence, MMT seeks to dispel the myth that government should treat its budget with similar constraints to a household or a firm. Through the lens of MMT, we will show how large-scale, transformational policies like the Green New Deal, Medicare-for-All, and college-free tuition are not only possible—they are within reach. As Dr. Stephanie Kelton, one of the leading proponents of MMT, explains: Our first question should not be, “How are we going to pay for it?” Rather, our first focus should be on the policy itself.

In order to fully understand MMT, we must first look at some traits of our current macroeconomic system. Scott Fullwiler calls these “Operational realities” and describes three truths that must be laid out. First, he says, is the accounting of real-world transactions. Banks can create loans and liabilities “Out of thin air”: without balances or reserves to “Fund” the loan. They can grow their balance sheets through loans and asset purchases. The second operational reality is the “Tactical logic for operations necessary to achieve particular, fundamental ends given a particular monetary regime.” Fullwiler notes that different monetary systems have different requirements, but for this article we will focus on the United States. We use a pure fiat currency with flexible exchange rates.

Hyman Minsky referred to the “Hierarchy of money,” and as Stephanie Bell puts it, “The State determines not only the unit in which all of the monies in the hierarchy are denominated but also influences the positioning of certain monies within the hierarchy.” As a currency-issuing government with flexible exchange rates, a country like the U.S. sits at the top of the hierarchy—above other nations that might use a currency union or a gold standard. Fullwiler looks at what is not possible given the accounting and tactical logic. This means that central banks, as monopoly suppliers of reserve balances to the banking system, “Must set an interest rate target […] but can only directly target the quantity of reserves if the target rate is set equal to the central bank’s remuneration rate on reserves.”

The only constraints we have on how we spend money are self-imposed. As Fullwiler puts it, “While the ability to ‘just spend the money’ is recognized in times of war or when a financial bailout is deemed necessary (by politicians, at least), MMT’ers want it to be just as obvious when the issue at hand is involuntary unemployment, crumbling infrastructure, children or retirees living below the poverty line, a major city devastated by natural disaster, and so forth. Please note that this is not to say that such a government should always spend simply because it can operationally—that would be ridiculous—but, rather, that there is no such thing as it not being able to ‘afford’ to put idle capacity to work; the appropriate constraint to consider is whether there is idle capacity in the first place, while also recognizing the obvious point that not all fiscal actions are equally efficient.” The real constraint is inflation.

Dr. Kelton, in a lecture about using MMT to address the “Pay-for” problem of the Green New Deal (GND), lays out three steps: 1) assess resource needs; 2) access resource and technological capacity; and 3) build in offsets as needed to free up or create resources needed beyond what is currently available. She notes that enacting Medicare-for-All will spur development of a GND. First, the savings of moving to single-payer would be about $200 billion per year. These savings would free up resources to use for other needs. Healthcare accounts for about 18 percent of GDP in the US, and making it more efficient would trim that number down—allowing us to use those resources in other ways. Offsets are only needed once society is constrained in resources. Her lecture notes three offsets specifically. The economy currently has about $530 billion worth of slack—meaning we could spend this much more without any additional resources or inflationary issues. If we add this to the savings from Medicare-for-All and eliminate the $650 billion we currently provide for fossil fuel subsidies (as we are moving to a green economy), we arrive at $1.38 trillion in offsets.

In subsequent talks, Dr. Kelton has noted that reforms to Wall Street and criminal justice would also free up real resources. She cites Senator Sanders’s proposal to cut incarceration in half by the end of his first term—which would free up over one million people who could help fight climate change.

Fiscal Versus Monetary Policy

To fully understand MMT, we must first look at the role government plays in our economic framework—the differences between fiscal policy and monetary policy. Generally, fiscal policy encompasses the methods by which the government taxes and spends money. Monetary policy, which primarily concerns the actions of the Federal Reserve, deals with interest rates and the amount of money in circulation. It is important to note that in our current system, the power the Fed has primarily consists of maintaining the overnight interest rate that banks can lend to each other. The Fed and the Treasury, while ultimately independent of each other, work partly in tandem to ensure that every payment authorized by Congress is carried out. This is done with reserves at the central bank and through the sale of Treasury bonds; the bank accounts of the recipients of government spending are credited. Changes in monetary policy do little to impact our day-to-day lives.

However, large changes in fiscal policy are necessary to move progressive policies forward, and there are two primary mechanisms to accomplish this. First, social spending can be used to decrease inequality and consequently eliminate volatility in the financial system. This volatility, according to Drehmann et al. 2018, stems from the unsustainable credit-driven accumulation of household debt, which reduces output in the economy when the debt is no longer able to be serviced. There is a clear link between high levels of economic inequality and these cycles of household debt accumulation. Kumof et al. 2015 noted that the rising income shares of high-income households were linked to an increase in the household debt-to-GDP ratio (particularly when it relates to poor households), which was subsequently linked to an increased risk of recessions (Id.). This explains why, according to the models of the Harvard Economist Monica Prasad in her book “America the Land of Too Much,” a one percent increase in the growth of social spending as a percent of GDP reduces the growth of household debt (percent of GDP) by 0.473 to 0.581 percentage points. Yet, despite the fact that policymakers have had many chances to fix these problems, according to the SWID dataset, income inequality in the US is at its highest point since the 1960s. And according to data from UC Berkeley Economists Gabriel Zucman and Emmanuel Saez, wealth inequality is at its highest point since the 1940s.

[NOTE: “Disposable Income Gini”/Gini coefficient is a measure of inequality after taking into account taxes and transfers. Since this takes into account the strength of the safety net and tax system, the fact that inequality is going up means the strength of those two systems has been going down. Thus, the need for policy to be reflective of the MMT framework. For more information on the Gini Coefficient, click HERE]

In other words, spending on progressive policies can eliminate the need of poor- and working-class Americans to access public goods through private-sector credit that has been shown empirically to be the wrong approach to ensuring macroeconomic stability.

The second mechanism to accomplish progressive goals is to utilize progressive taxation to eliminate the imbalance of power between the working-class and wealthy. This imbalance of power is not only harmful to the working class but also to long-term economic growth. This idea can be inferred from the link between economic inequality and inequality of opportunity. In 2016, researchers at the Rand Corporation conducted a meta analysis of the literature and found that economic inequality has a negative relationship with opportunity—because it creates an unequal playing field between the rich and poor in terms of access to important endowments such as education. Additionally, income inequality can negatively impact political equality, which compounds these negative effects by preserving institutions built on this inequality. According to a study by Martin Gilens and Benjamin Page of Princeton University, there is a close correlation between the policy preferences of economic elites and the policies of the US government. This bias in policy preferences toward wealthy donors has a tangible effect on countercyclical redistributive institutions. Larry Bartels at Vanderbilt University found that the political bias in favor of the policy preferences of the most affluent citizens has led to a decline in equilibrium social spending by 10-15 percentage points. When reconciling these realities with MMT, under this framework, fiscal policy is not just about funding social programs; It is also about utilizing the power of the state to create an environment of economic inclusiveness for all ethnographic groups in the society.

Orthodox and Heterodox Views: Where the System Went Wrong

Throughout our nation’s history, we have seen various interpretations of economic philosophy—often inspired by the work of other countries. Orthodox thinking—largely attributed to economists like Adam Smith, F.A. Hayek, and Milton Friedman—was the basis on which the US built its economic system before the Great Depression. After the collapse of the stock market in 1929, ideas brought forth by J.M. Keynes were put into action by President Franklin D. Roosevelt as the ideas of neoclassical and Keynesian economics merged. President Hoover, in the wake of the Great Depression, maintained that the government should not interfere in markets or provide economic relief. More than 20 percent of Americans were unemployed at this time. President Roosevelt enacted sweeping changes after his election in 1932. These included regulating banks and the stock market, creating the Social Security system, and forming the New Deal. The US has primarily relied on methods of Keynesian and Post Keynesian thought post-WWII.

Where Are We Now?

Congress is tasked with budget implementation under the Constitution. The House, Senate, and White House all propose budgets, and joint-committees are formed to negotiate discrepancies. Once an omnibus budget is agreed upon, it is presented to the president for signature. As mentioned earlier, the House has enacted a PAYGO policy, and the Senate is prohibited by procedure from enacting anything that will create a budgetary hole within a decade. Enter austerity politics. Austerity measures, as we know them, deal with the system of raising taxes or cutting spending to balance the budget. This is where the rubber meets the road for many policy ideas. The first question for any politician proposing large-scale changes (GND, Medicare-for-All, etc.) becomes, “Are you going to raise taxes or cut spending to pay for this program?” At the state and local level, that question makes more sense—as state and local governments are constrained by revenue. At the federal level, we are currently running a trillion-dollar deficit (so much for the Republican tax cuts paying for themselves, huh?). On the Right, budget slashing is the preferred tool of the trade. Programs like healthcare, education, entitlement and welfare programs, and criminal justice are first on the chopping block. But these programs are essential to a healthy, happy, and prosperous society. The further we dig ourselves into a hole through austerity methods, the more poverty, crime, and societal unrest we will see. We must stop using these important programs as wealth-transfer-springboards for the rich. We must stop thinking of government deficits as a fundamental problem and decouple our tax and spending fights; PAYGO intertwines them. These need to be separated so we can think about whether we need offsets (tax increases) or not. PAYGO makes us start with the presumption that all new spending needs to be fully offset. That is bad economics and bad public policy.

Conversely, on the Left, a standard response to pay-fors come in the form of a wealth tax, higher corporate income tax rates, or taxing transactions on Wall Street. While these methods could help to shrink the social and racial wealth gap, they are not necessary to pay for programs. With this in mind, let’s go back to the original question. Are you going to fund new programs by raising taxes or cutting spending? The short answer is this: Neither.

Where Do We Go From Here?

Under the theory of MMT, we must completely rethink our idea of taxes. “So long as government can impose and collect taxes it can ensure at least some demand for a nonconvertible currency. All it needs to do is to insist that taxes be paid in its own currency. This ‘promise to accept in tax payment’ is sufficient to create a demand for the currency: taxes drive money” (Wray, 72). Taxes are not the method by which the government spends—they are merely a way to ensure the stability of a nonconvertible currency. Indeed, “Government must spend (or lend) the currency into the economy before taxpayers can pay taxes in the form of currency. Spend first, tax later is the logical sequence” (Wray, 141). Additionally, MMT proponents recognize another reason for taxes: To reduce and stabilize aggregate demand. Taxes reduce private-sector purchasing power and consumption of harmful goods and services like tobacco. Without taxes, several macroeconomic problems would come into play, including large inflationary pressures. We must move past the cognitive dissonance and accept this simple truth: Taxes do not “pay” for anything (at least at the federal level). Simple keystrokes on a computer do that.

Explain MMT to a classical economist or a standard citizen and you’ll typically get the same response: “Won’t more money in the economy lead to inflation?” This is the million-dollar question, and it requires a thorough response. While some inflation is necessary to increase, say, a teacher’s compensation, we always look at ways to limit inflation while increasing employment. While no other country has fully implemented a standard MMT approach, there are a couple notable examples of expanding the circulation of currency detrimentally: Zimbabwe and the Weimar Republic. As Wray notes, Zimbabwe “was going through a tremendous social and political upheaval, with unemployment reaching 80 percent of the workforce and a GDP that had fallen by 40 percent” (Wray, 262). Further, unsuccessful land reform led to the collapse of food production. The government then relied heavily on food imports and IMF lending—ultimately leading to external debts. Food was scarce, and the government and private-sector were battling for a small supply of resources, pushing prices up. This ultimately led to hyperinflation. In the Weimar Republic, austerity measures were not feasible to fund reparations from WWI. “The government believed that it was politically impossible to impose taxes at a sufficient level to free-up resources for exports to make reparations payments, so instead it relied on spending. This meant government competed with domestic demand for a limited supply of output—driving prices up” (Wray, 261). The domestic producers were forced to borrow abroad, in foreign currency, to buy necessary imports. Domestic currency was depreciated in large part due to rising prices and foreign borrowing. Both examples failed in large part due to social/political unrest and an inability for the government to implement policies that would absorb their additional money supply.

So, let’s get back to inflation. As Dr. Kelton notes, any payments authorized by Congress will be cleared by the Federal Reserve. What matters is the economy’s capacity to safely absorb any increase in spending. There are a number of methods to mitigate inflationary concerns with an increase in spending, which we will outline further.

MMT and Progressive Policies

As the Overton Window shifts and progressive, populist ideas become more and more popular, we should look at how MMT could impact several of the biggest programs on the national stage.

Federal Jobs Guarantee

A federal jobs guarantee (FJG) would be an important targeted approach to creating a better income distribution, increasing consumption, and improving the stability of the US economy. Pavlina Tchernova of the Levi Economics Institute at Bard College noted in 2012 that these effects can occur with a universal job guarantee by utilizing an Employer of Last Resort (ELR) approach. This would increase macroeconomic stability by targeting spending toward employing everyone that is not able to get a job in the private-sector and thus creating true full employment. It can also help to reduce the volatility associated with boom-and-bust cycles by acting as an automatic stabilizer during recessions. Additionally, according to a study by Scott Fullwiler of the University of Missouri-Kansas City, the guarantee can also increase private-sector growth through consumer spending and human capital accumulation effects associated with new skills and wage incomes generated from the public-sector. Modern Monetary Theory can serve as a catalyst for an FJG by providing important justifications for the initial allocation of spending towards those programs that can be tailored to the individual civic and economic needs of the community.

The main benefit—and the reason this would mitigate inflation—is that it would essentially create a “job buffer” that expands or contracts based on economic circumstances. Federal employment would grow in recession and shrink in expansion, which counteracts fluctuations in private-sector employment. It is estimated that implementation of such a program would put net spending by the government at well under one percent of GDP. After its financial crisis in 2001, Argentina implemented a program known as Plan Jefes y Jefas de Hogar Desocupados (Program for Unemployed Male and Female Heads of Households). Daniel Kostzer, who studied the program, noted that it amounted to under one percent of GDP, and “paved the way for a reduction of the contractionary effects that otherwise would have caused a catastrophic devaluation of the currency.” The program ultimately employed five percent of the population and successfully found useful work for participants. “Jefes reduced social unrest, (sic) and provided demand for private sector production” (Wray, 237).

In addition to a job buffer, high inflation problems can be decreased by reducing indexing, stabiliz[ing] production, solving supply constraints, and quell[ing] social unrest (Wray, 262-3).

Medicare-for-All

Medicare-for-All would greatly benefit from an MMT framework. The empirical support for a single-payer healthcare system to fix the original deficiencies of the Affordable Care Act is such that it is the unrivaled solution to address the problems of a healthcare system that prioritizes profit over the quality of life. By specifying MMT as the economic theory to utilize in funding a single-payer system, we would erase the need to utilize any form of regressive taxation as a funding source. According to an analysis by Gerald Friedman of the University of Massachusetts-Amherst, a Medicare-for-All plan that primarily uses progressive taxation would greatly improve the household income of the bottom 95 percent of Americans. Additionally, raising taxes on individual wealth can help to counteract the political and economic fight that has been waged by decades of lobbying against healthcare reforms.

Even though they are typically thought of in different ways, a true Medicare-for-All proposal would work hand-in-hand with the FJG/ELR component of a GND. In theory, under plans where the federal government provides free-at-point-of-use, single-payer healthcare, jobs would be lost in insurance, medical sales, and the pharmaceutical industries. Any wholescale FJG/ELR would provide job retraining for those who lost their jobs in these industries or, say, a coal mine. The government would also provide additional training for those in the medical field as we transition to our full population utilizing preventative and chronic care.

Green New Deal

The Green New Deal has been talked about in various ways over the past several years. Resolutions were introduced by Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and Senator Ed Markey (H. Resolution 109 and S. Resolution 59, respectively). These resolutions lay out basic plans to fund green infrastructure, create a federal jobs guarantee, reduce pollution and emissions, guarantee education, implement cleaner transportation, and a host of other issues—within a decade. As the 2020 presidential race ramps up, more and more Democratic hopefuls are establishing their own GND proposals. Senator Bernie Sanders recently released his campaign’s GND platform, and it follows many of the previously mentioned prescriptions with more clarity. Any GND proposal must include an ELR/FJG component to offset inflationary pressures, and we need to hold politicians’ feet to the fire to prevent the coming climate disaster.

Under MMT, the United States would be able to fully fund and implement all provisions of a GND. We need to shift the way we think about funding a GND proposal. We do not need tax increases or budget cuts; We need to find ways to allocate resources where there is room in the economy to accommodate them. Though it will be difficult to carefully manage the inflation risk as we transform our entire economy within a short timeframe, we must restructure our thinking of this issue if we want to enact a fully implemented GND.

Tuition-free College

Several states have already taken steps to provide free in-state or community college tuition to its citizens. However, with the average cost of college for an in-state school at around $25,000 per year and trade programs being decimated in primary schools, college is unattainable for a large portion of our population. Even those who are fortunate enough to get through college are likely to come out with crippling student loan debt. Federal student loan debt has recently risen to over $1.6 trillion, and it is growing by the day. This hampers our economy and prevents debt-carriers from starting families, creating businesses, and buying homes.

A study from the Levy Institute found student loan debt cancelation could boost GDP over a 10-year period by up to $1.08 trillion, reduce the unemployment rate by up to 0.36 percentage points, add up to 1.5 million new jobs per year, and have an insignificant effect on inflation rates.

It is nearly impossible to put into context the social benefit of a higher-educated population. Breaking the cycle of poverty and allowing anyone who wants to attend college and create a better life for themselves is one by-product. An increasingly educated society would inevitably lead to advances in science, medicine, poverty-alleviation, healthcare, decreases in crime, and boost the economy. A study by the Urban Institute found significant reductions for those receiving welfare benefits who have a college education. Additionally, their data show a substantial decrease in unemployment for those with a college degree versus those with a high school degree.

Conclusion

In order to facilitate truly transformative progressive policies, we need to change the way we look at the federal budget. If we can provide policies that include necessary resources to mitigate and cushion inflationary pressures, the United States government can fund whatever is needed to usher in programs that combat climate change, ensure high-quality education, provide a full social safety net and universal healthcare, and fix our crumbling infrastructure. The goal of government is to provide for its citizens; The government is not a business, and we need to stop thinking of it as one.

References:

Modern Money Theory: A Primer on Macroeconomics for Sovereign Monetary Systems by L. Randall Wray (2016).

Macroeconomics by William Mitchell, L. Randall Wray, Martin Watts (2018).

Going With the Flows: New Borrowing, Debt Service and the Transmission of Credit Booms by Mathias Drehmann, Mikael Juselius, Anton Korinek (2018).

Inequality, Leverage, and Crises by Michael Kumhof (2015).

Lectures from Dr. Stephanie Kelton at Stony Brook and the New School.